Hello everyone, today we will learn about Injection vulnerabilities such as SQL and Command Injection. First, we will learn the concept, and then we will move to the practical part where we will inject the vulnerable code and test it on the website. Once we learn Injection, we will review the insecure code to make it secure. We will be working with a Django project called “timesheet.” So be ready and make sure to clone the project source code from GitHub here: “https://github.com/0xorone/week9.git". Feel free to clone the project locally in your desired folder or directory. You will have to perform everything practically with me. For now, do not worry about how to set it up if you have no idea. I will explain all the steps below. But first, we will understand the Injection concept here.

You may have a question about why we are learning Injection first when we know Broken Access Control is the most important because it is ranked #1 in OWASP 2025?

Well, the answer is that Injection is very easy to understand, and most likely everyone who is in cybersecurity already knows SQL Injection and Command Injection. So I chose it to start with something simple, and then in the future we will move to the next items in the list. The thing to note here is that maybe we cannot cover all Top 10 vulnerabilities in the 12-week plan, but we will try to cover as many as we can.

OWASP A03:2021 -> Injection

The Injection vulnerability ranked at #3 in the OWASP 2021 survey, and it is now ranked at #5 in the 2025 survey. Many new vulnerabilities came above it, which is why it went down to #5. Let us first understand the injection flaws.

Understanding Injection Flaws

In this post, we are going to cover injection flaws, which are among the most famous and attractive to hackers. Here, we are going to look at some of the most common forms of injection flaws, particularly SQL Injection and OS (Operating System) Command Injection. We need to understand what they are so we can see how they become a problem. That then helps us understand the solutions. We will then look at parameterization, a method of stopping injection, especially in SQL commands.

Injection starts with an interpreter, a program that takes input and performs actions based on it. Interpreters can be complex and difficult to defend against injection attacks. If this weakness exists in your website, then it can often result in a complete loss of confidentiality, integrity, and even availability. So it does not really get any worse. This is the first vulnerability we are looking at and also the first of many occasions when we are going to talk about the cause, which is using untrusted input. Untrusted data is any data that you use in your website that comes from outside your website. That means data from any part of a web request, from third-party services, or from other web services that you own. Even data from administrators of your own website could be potential sources of attack.

There are a number of different types of injection, including SQL Injection aimed at databases, OS Command Injection targeting operating system requests, LDAP Injection used to query Active Directory, and NoSQL Injection for communicating with NoSQL databases. We are going to talk about the first two here, but they all share some common features and defenses.

Attacking and Defending SQL Injections

So SQL Injection is one of the most common forms of injection. Here, we are talking specifically about an attacker’s ability to alter commands being sent to a database that uses SQL syntax. There are a variety of databases that use this, common ones being MySQL and SQL Server. The SQL you send to the database will be interpreted by the software that runs it, and as we have discussed, the interpreter is the point at which we can have a problem. It is useful to see a SQL statement as a set of commands and a set of parameters being sent to the interpreter. Looking at a simple SELECT, we are getting a set of columns from a table where a set of criteria is true.

SQL Statement:

SELECT userID

FROM Users

WHERE userName = 'admin' AND password = 'admin'

This can be split into commands and parameters. Here, SELECT is the command, and the column names are the parameters being passed to it. FROM is the command, and the table we are looking at is the parameter we are passing there. Finally, the WHERE clause is a command, and within that, AND is also a command, with the parameters making up the rest of the text.

When we see these statements in code or stored procedures, it is common to hardcode both the column names and the table name. That means we are restricting the results in a predictable way. Let us assume that the SQL statement we have just seen was created by the following Python code, where the parameters going to the WHERE clause come from user input. This statement is returning a userID only when the correct username and password are entered, so it could be code used to log someone into a website. Incidentally, this statement suggests we are storing passwords in the database without any protections. Such example:

userName = "admin"

password = "admin"

query = "SELECT userID"

FROM users

WHERE userName = "'+ userName +'"

AND password = "'+ password +'"

The query looks like this:

SELECT userID

FROM Users

WHERE userName = 'admin' AND password = 'admin'

We will look at that later, maybe in the next vulnerability, “Preventing Sensitive Data Exposure.” So the separation of commands and parameters is really important here. If your website can accept input for a SQL command, then it should always be interpreted as parameters. If an attacker can send data that contains commands and have them interpreted as commands, then we will have a problem. If they can do that, then they can potentially read, write, or delete any of the data in the database, breaching confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

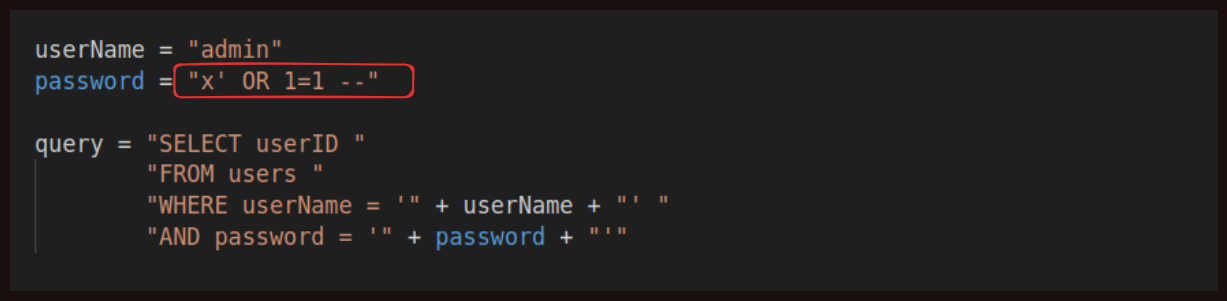

SQL Login (SQL Injected)

If the user entered this value as the password, then they would be entering the command as one of the parameters. We are saying “x” is our password, but then we are also passing a single quote, which ends a string value in SQL. The query looks like this:

If the user entered this value as the password, then they would be entering the command as one of the parameters. We are saying “x” is our password, but then we are also passing a single quote, which ends a string value in SQL. The query looks like this:

SELECT userID

FROM Users

WHERE userName = 'admin' AND password = 'x' OR 1=1 --'

After that, we are entering a command, the word OR, with two hyphens used to comment out any further syntax. Used in our Python code, you can see that we have changed how this statement works. Now it will return the userID when the password is “x,” which almost certainly is not the password, OR when 1 equals 1, which will always be true. So this will always return a userID, effectively allowing someone to log in without the correct password. Finally, we have the two hyphens to comment out the final single quote, which would have caused a syntax error. In this case, we would be free to enter any valid SQL syntax in the password field and have it executed by the interpreter.

Object-relational mappers, also known as ORMs, let you write Python commands that result in SQL queries. They are experts at parameterization, which involves taking values and ensuring they are used only as parameters to commands. ORMs prefer methods that enforce this parameterization. This means we are not writing our own SQL queries in code. Instead, we use methods in the ORM to do that for us, and they ensure that the values passed to them are used strictly as parameters. They enforce the separation between commands and parameters and are a very useful defense against SQL Injection.

Attacking and Defending Operating System Command Injections

Moving on to Command Injection, we have an example of a command. This is a piece of Python that takes a request and performs a network ping to check that the server at that address is running. You could see this as a potentially useful piece of admin functionality to check the health of servers.

Command Injection Statement:

import subprocess

serverIpAddress = "127.0.0.1"

pingCmd = "ping -c 1 " + serverIpAddress

subprocess.Popen(pingCmd, shell=True)

And it will ping normally like:

ping -c 1 127.0.0.1

In this case, the value coming from the user is the value serverIpAddress. We have the ping command, some hard‑coded parameters for it, and then we have the user‑supplied parameters at the end. If the user supplies a valid IP address, then the command will work as expected. We are taking untrusted user input and allowing that to be used before it gets passed to an interpreter. The interpreter, in this case, is the operating system, which is called by subprocess. If instead of an IP address we start passing operating system commands, then we will start to see the injection risk.

Command Injection (command injected):

import subprocess

serverIpAddress = "& dir"

pingCmd = "ping -c 1 " + serverIpAddress

subprocess.Popen(pingCmd, shell=True)

Here, we are passing in the value & dir, which in the Windows operating system allows a further command to be issued. The command dir lists the contents of the current directory. A similar thing could be done on Linux using a semicolon to allow another command, and the ls command to list directory contents.

It is worth considering defenses for other injection risks, such as OS Command Injection. We should prefer libraries instead of creating raw operating system commands. Our example showed a network ping using a raw command passed to the operating system. For a ping, there are Python packages such as tcping that allow you to make ping requests from your code, which use Python to make those requests instead of deferring to the command line. This significantly reduces your risks. If you are making raw operating system calls, then seriously consider other options.

We have also mentioned defense‑in‑depth in previous weeks and many times before. The other main defenses here revolve around input validation, similar to XSS. In short, we are going to want to check that data coming from requests is in a format that we expect.

Injection Attacks Practical!!

We are going to look at an application called “timesheet” that is used by XYZ company employees to track their time. It is an internal application for the business, created by a development team that has long since left to work on other websites. It is your job to make some security improvements. The website is written using the Django framework, but the exact technology used is less important than the thought we are going to put into the website security. The security controls we will be putting in place are similar no matter what framework you choose to use. We are going to start by looking at a field that might allow us to issue our own commands to the database, which means it is vulnerable to SQL Injection. We will view the underlying code to understand where the problem is, and from there, we will start to implement the solution.

Note: I don’t own this project “timesheet”. All the respect and credits goes to the original author.

Setting Up the Environment

Here are the steps to follow in order to set up the pre‑written vulnerable Django project locally. First, clone the project to the “week9” directory (or anywhere you prefer), but make sure to follow a clean and organized structure for storing code on your local system.

Clone from GitHub using this command:

git clone https://github.com/0xorone/week9.git

make sure git is installed on your system. Once the code is cloned into the directory where you are working, you will see two directories. you have to start from “StartHere” and the second “CompleteCode” directory contain updated version of the vulnerable “timesheet” code.

Now you now have to follow these steps:

- Inside the timesheet project folder, create a virtual environment using the command:

python3 -m venv venv - Activate the virtual environment using the command (on Linux):

source venv/bin/activate. If you have Windows, I hope you know how to activate it. Otherwise, please search it on Google. - Install the

requirements.txtfile using the command:

pip install -r requirements.txt - You will also see the

manage.pyfile in the directory. If not, first go into the timesheet directory and you will find it there. - Then run:

python3 manage.py runserver

You will see the server start (maybe with a warning). It is just a warning, but we will fix it first. (Below is warning msg):

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

You have 18 unapplied migration(s). Your project may not work properly until you apply the migrations for app(s): admin, auth, contenttypes, sessions.

Run 'python manage.py migrate' to apply them.

November 45, 2030 - 05:55:24

Django version 5.2.8, using settings 'timesheet.settings'

Starting development server at http://127.0.0.1:8000/

Quit the server with CONTROL-C.

Press Ctrl + C to stop the server.

6. First, we need to make migrations to make the project run smoothly. Run this command:

python3 manage.py makemigrations

- Next, we need to apply the migrations using the command:

python3 manage.py migrate

- Now, before testing, we need to create an admin or superuser for the project using this command:

python3 manage.py createsuperuser

Then enter the information such as “admin” for both username and password. If you see the warning “the password is too common,” of course it is (do not use common passwords), but since we are testing locally, there is no issue. Just type “y” and continue. When it asks for an email, you can simply press Enter to skip it.

- We also need to create some normal users for testing purposes using the Django shell:

python manage.py shell

This will open the REPL. Copy and paste the following lines one by one:

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

User.objects.create_user(username="user1", password="pass123")

Additionally, create another superuser:

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

User.objects.create_superuser(username="admin2", password="pass123")

and then exit REPL using this command exit()

- Now run the server again using:

python3 manage.py runserver

Access the login page in your browser using the default URL:

127.0.0.1:8000/login

and enter your credentials. In my case, I used admin:admin.

Note: Make sure to go directly to the /login page (above given) because there are some errors on the project’s home page when you visit directly.

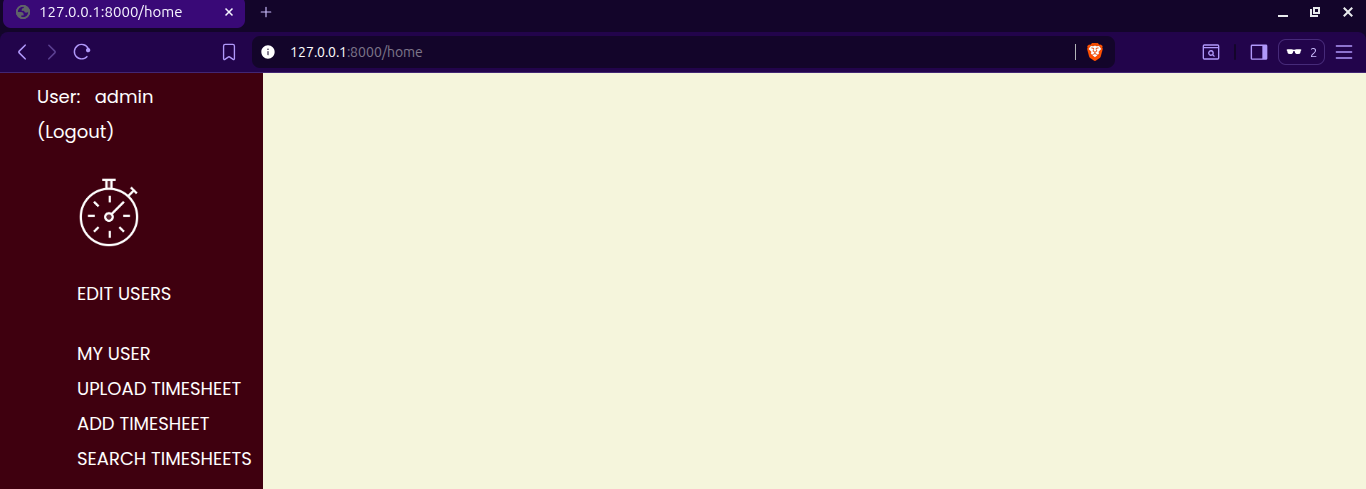

- Now you will see the homepage.

Note: Please note that the code is not written very well, and some features may not work. For example, if you try to visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/ or click EDIT USERS, MY USER, etc., it may cause errors. Do not worry, we will make the code work for the parts where it is important.

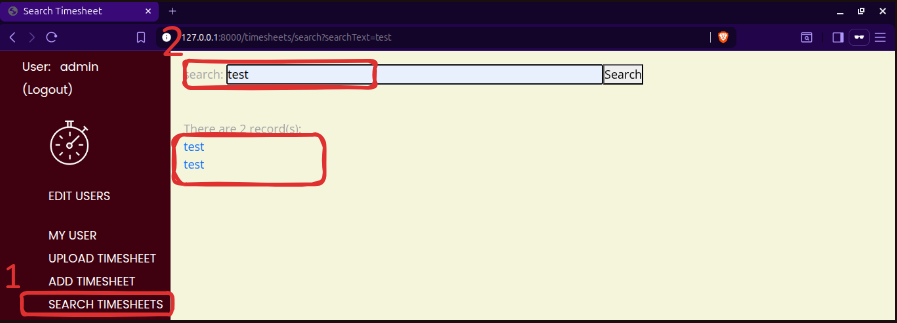

Now, here comes the most important and practical part. We have our timesheet website. We have logged in using the admin:admin credentials, and we are at the function “SEARCH TIMESHEETS”, which allows us to search for timesheets based on the notes entered against them.

We can “Add Timesheet”, for example, I added test. We will start with a simple search using “Search Timesheet” and see that it returns a list of timesheets as hyperlinks. If we click on one, we can view the details. It is a nice, simple search.

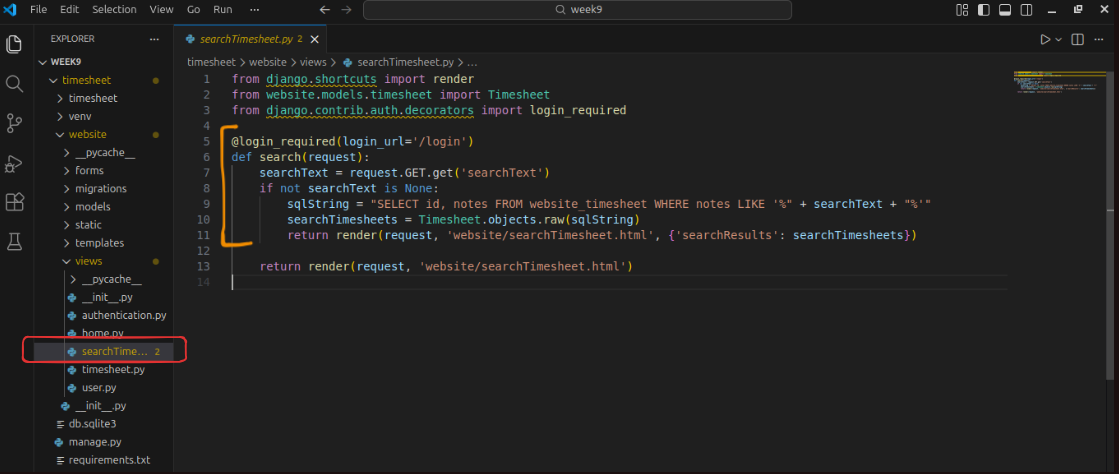

Let us take a look at the code being used to run that. We have a searchTimesheet view, with a function named search. There is a decorator (@login_required) to ensure that a user has to be logged in to be able to use it, which is good. We are getting the user-entered searchText, and then creating a SQL string containing it.

A typical result of this operation, if we searched for test, would be the following SQL statement.

SELECT id, notes

FROM website_timesheet

WHERE notes like '%test%'

Creating a SQL string like this is, unfortunately, one of the easiest ways to introduce a SQL Injection vulnerability. The id, an integer, and notes, a string value, are being returned by this query. Keep that in mind as we go back to the website. Now we are going to search for the following string.

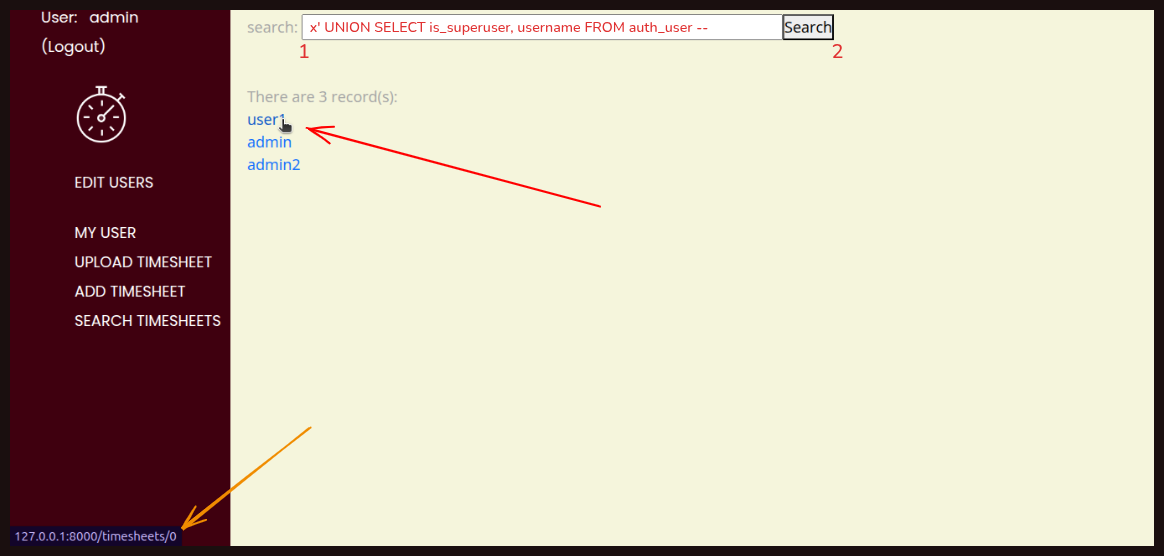

x' UNION SELECT is_superuser, username FROM auth_user --

We are closing the SQL string with a single quote, then using the UNION command to join any data we would have received with two values from the auth_user table, a standard table in Django. These two values are a bool, which can also be an integer 0 or 1, and a string, so they match the format of the id and notes fields. There are also two hyphens used as a comment. In our code, the SQL statement we are creating becomes this. We have the original SELECT, and we are combining that with the SELECT from the auth_user table. Below, we are trying to put the SQL injection in the search bar, and it is giving us the result:

The result not only gives us a list of all users for this website, but if we hover over a link, we can see the value 0 for a regular user, and if we hover over

The result not only gives us a list of all users for this website, but if we hover over a link, we can see the value 0 for a regular user, and if we hover over admin, or admin2 we can see that they are a superuser. This allows us to identify what type of user each one is.

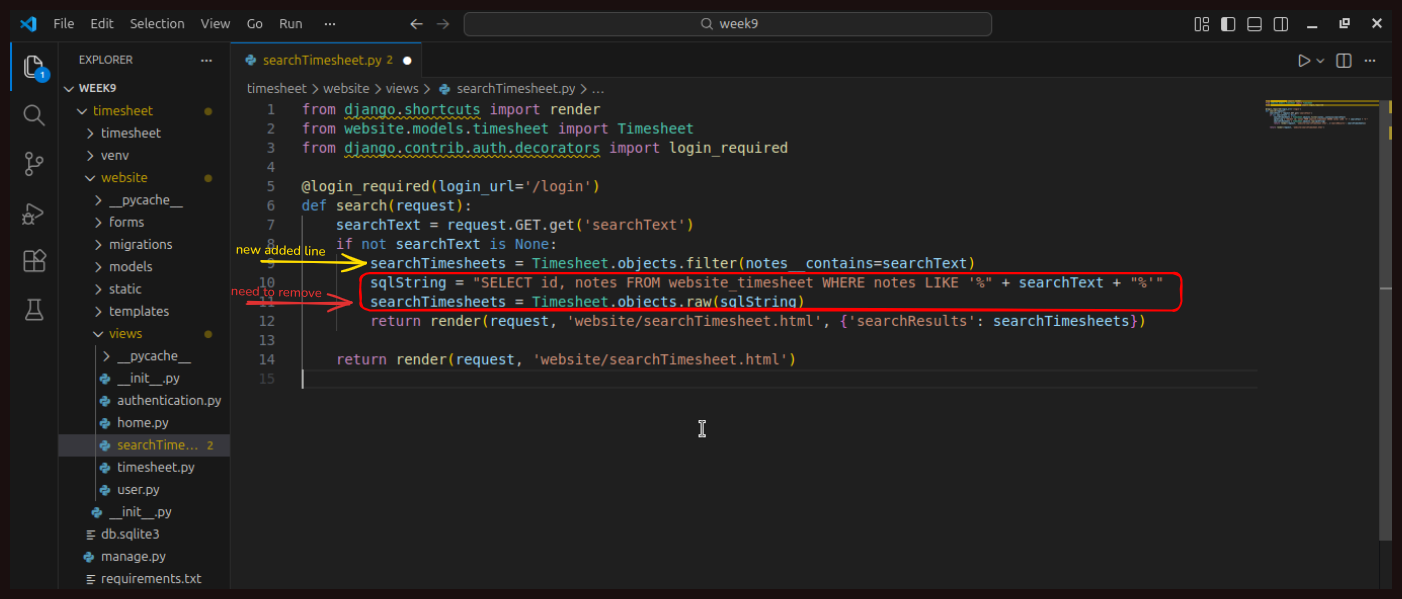

With a little creativity, you could use this to query or even delete almost any data in the database. The solution to this is relatively simple. Django has its own ORM, which is designed to prevent SQL injection by enforcing a separation between commands and parameters. We will add a new line, searchTimesheets = Timesheet.objects.filter(notes__contains=searchText), to achieve this while still performing a wildcard search. Before we remove the vulnerable lines of code, it is worth noting that we were already using the Django ORM.

The mistake was that we passed raw SQL into it, which is dangerous.

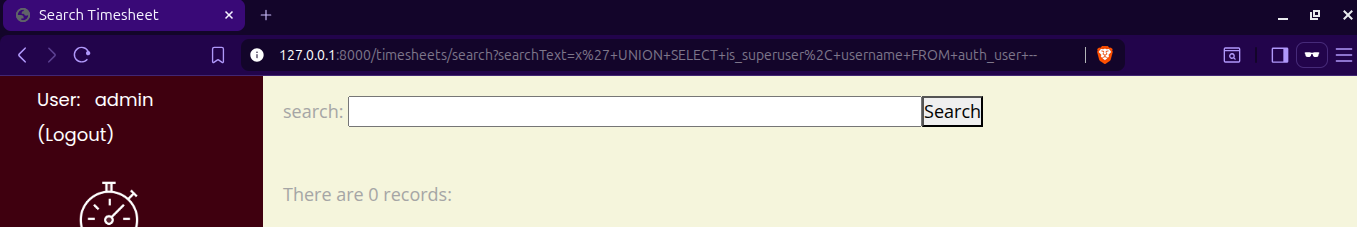

So we will remove those two lines. After saving the changes and going back to the search page, we try searching again using our injection string:

x' UNION SELECT is_superuser, username FROM auth_user --

This time, we receive no results.

We have now put a good defense in place against SQL injection. Searching for “test” again gives us the correct result. If we really do want to write our own raw SQL, there are still options available, and there are many more possibilities you can learn about online.

We have now put a good defense in place against SQL injection. Searching for “test” again gives us the correct result. If we really do want to write our own raw SQL, there are still options available, and there are many more possibilities you can learn about online.

To sum up this post, we have studied SQL injection and how to defend against it. A key indicator that a SQL injection vulnerability existed was that we were creating a raw SQL query as a string in our code without anything to ensure that parameters were handled correctly. The primary solution was to use an ORM, which automatically writes secure SQL queries for us, without the risk of injection. ORMs are very common for interacting with databases, and they are excellent at preventing this type of attack. There is also an option to use parameterized queries in Python, which look similar to raw SQL queries, but include additional code to ensure that parameters are processed safely. The important concept here is that we can never trust input from the client; we have to assume it could be malicious. SQL injection is a major risk to any website, and we have just learned the key defense to protect against it.

That’s it, everyone, for today’s post. I hope you learned something new and gained a basic idea of how injection vulnerabilities work. The best part is that we explored everything by reviewing and testing the code practically. I highly recommend that you try it yourself. Do not just read but implement it. If you have any questions, recommendations, improvements, or corrections, feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn at https://linkedin.com/in/aziz-u000. See you next week.