OWASP Top 10 and Secure Coding Principles

Hi Everyone welcome back again. You should be proud of yourself. We came so far. Till now we have covered the basics of Python including the two most powerful Python web application frameworks such as Flask and Django. Now before moving to real world code analysis of Django based web applications, first we need to learn and understand OWASP Top 10 and some basic coding principles which we will cover today. Then from next week we will start learning real world Python code review of insecure and secure coding. So for now we will be learning the basics of OWASP Top 10 and basic coding principles to follow. This post will be more theoretical. Some of the code examples may be taken from external resources and from source code of different applications just for understanding the concepts and to make you better prepared for the next remaining course (Note: sometimes developers write with complex naming and structure so I will enhance the code snippets with AI for better understanding). So sit back and relax we are going to dive in.

Why OWASP Top 10 Matter!!

OWASP Top 10 is very important. The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) maintains this list of the most critical security risks to web applications. They are not just limited to web application vulnerabilities, they also cover mobile and GenAI or LLM Top 10 vulnerabilities as well. These are real vulnerabilities that are actively being exploited in the wild right now. Every time you hear about a data breach on the news, chances are it involved at least one of these vulnerabilities. They collect and score this list after a lot of research and learning from those data breaches that keep happening.

So let’s explore each item in the OWASP Top 10 list based on the 2021 report.

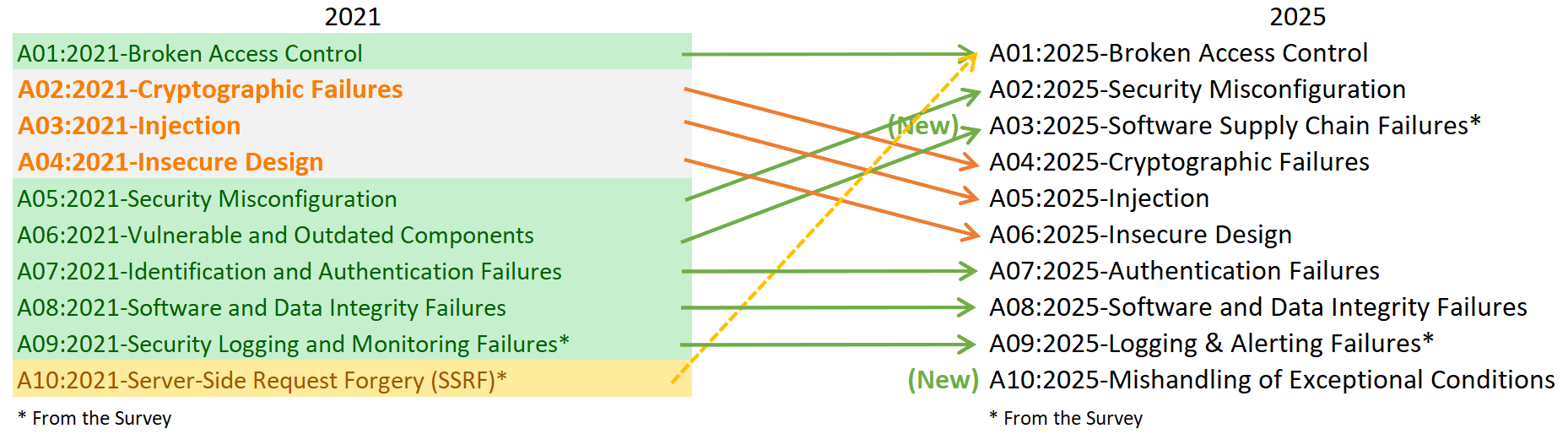

Note: This list was released in 2021. We also have the 2025 list, but it is not yet fully published and will be released very soon. It contains many new vulnerabilities compared to 2021. You can see the comparison figure below.

Let’s understand each of these 10 vulnerabilities in detail with practical real world web application code examples.

OWASP A01:2021 -> Broken Access Control

Access control refers to a process that ensures only authorized users have access to certain types of data. Broken access control typically leads to unauthorized information disclosure, modification, or destruction of data, or performing a business function outside the user’s limits.

Elevation of privilege Acting as a user without being logged in or acting as an admin while logged in as a normal user. Horizontal privilege The user gets access to different resources other than the one intended for them.

Broken access control can also lead to unauthorized access to sensitive links and web pages or files on a website due to the fallacy of security through obscurity (the belief that anything on a website that isn’t linked or indexed cannot be found). I see this mistake many times. Sometimes you are focused on building features quickly, and you forget to check, should this user actually be allowed to do this? Let me show you what I mean with a Django code example.

here is the vulnerable code:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from .models import Document

def view_document(request, doc_id):

document = get_object_or_404(Document, id=doc_id)

return render(request, 'document.html', {'document': document})

What’s wrong with this? Well, any authenticated user can view ANY document just by changing the doc_id in the URL. There is no check to see if they actually own that document or have permission to view it. This is a classic case of Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR), and it’s scary how common it is.

Now, here’s how we should actually write this code:

from django.shortcuts import render, get_object_or_404

from django.core.exceptions import PermissionDenied

from .models import Document

def view_document(request, doc_id):

document = get_object_or_404(Document, id=doc_id)

# Check if user owns the document or has permission

if document.owner != request.user and not request.user.has_perm('app.view_document'):

raise PermissionDenied("You don't have permission to view this document.")

return render(request, 'document.html', {'document': document})

Even better, Django gives us decorators and mixins to handle this more elegantly. But for now we want to understand the basic concept. The principle here is simple, never trust that just because a user knows an ID or URL, they should have access to it. Always verify. This is what we call the principle of least privilege, give users only the minimum access they need, nothing more.

Mitigations

- Deny by default i.e every user starts with the minimum privileged functions

- Enable RBAC (Role-Based Access Control)

- Disable web server directory listing and ensure file metadata and backup files are not present within web roots

- Constant Testing and Auditing of Access Controls

OWASP A02:2021 -> Cryptographic Failures

Cryptographic failures used to be called Sensitive Data Exposure. This focuses on failures related to cryptography that often lead to exposure of sensitive data. These failures happen when applications don’t properly protect sensitive information through encryption, which can lead to data breaches and compliance issues. This is about protecting sensitive data both when it’s stored in your database (at rest) and when it’s traveling across the internet (in transit).

Attack Scenario: A site doesn’t use or enforce TLS for all pages or supports weak encryption. An attacker monitors network traffic and steals the user’s session cookie. The attacker then replays this cookie and hijacks the user’s authenticated session, accessing or modifying the user’s private data.

Why Insecure!!

Weak Encryption Using outdated or weak cryptographic algorithms that can be easily broken.

Plaintext Storage Transmitting or storing sensitive data without encryption protection.

Poor Key Management Inadequate protection of encryption keys and certificates.

I took this code from a vulnerable app where passwords were stored like this (Not Secure):

import hashlib

def store_password(username, password):

# Using MD5

hashed = hashlib.md5(password.encode()).hexdigest()

User.objects.create(username=username, password=hashed)

MD5 is not encryption, it’s a hashing algorithm, and it’s been broken for years. You can crack MD5 hashes in seconds using rainbow tables. Even worse, I have seen passwords stored in plain text. If you are doing either of these, please stop immediately. Django’s first priority is security and it offers many good tools. Here’s how Django handles passwords securely and why you should always use the framework’s built-in tools:

from django.contrib.auth.hashers import make_password, check_password

def create_user_secure(username, password):

# Django uses PBKDF2 by default with SHA256. It also automatically handles salting

hashed_password = make_password(password)

User.objects.create(username=username, password=hashed_password)

def verify_password(user, password_attempt):

# timing-attack resistant

return check_password(password_attempt, user.password)

Django’s default password hasher uses PBKDF2 with SHA256, includes a random salt, and uses 600,000 iterations. This makes it computationally expensive to crack passwords even if your database is compromised. But passwords aren’t the only sensitive data. What about API keys, database credentials, and secret keys? Never hardcode these in your source code (not a secure way to do it):

SECRET_KEY = 'django-insecure-h@rdcoded-key-123456'

DATABASE_PASSWORD = 'MyP@ssw0rd123'

API_KEY = 'str_secure_abc123xyz789'

Instead, use environment variables and tools like Python Decouple or Django Environ:

import os

from decouple import config

SECRET_KEY = config('SECRET_KEY')

DATABASE_PASSWORD = config('DB_PASSWORD')

API_KEY = config('API_KEY')

# also ensure HTTPS

SECURE_SSL_REDIRECT = True

SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE = True

CSRF_COOKIE_SECURE = True

The principle here is defense in depth. Even if one layer fails, like someone gaining read access to your code repository, your secrets are still protected because they are stored separately.

Mitigation (as per OWASP 2025)

Modern Algorithms Use current cryptographic standards like AES-256 and RSA-2048+ Enforce TLS 1.2+ Require secure transport protocols for all data transmission Secure Key Storage Implement proper key lifecycle management and protection Transport Layer Security A cryptographic protocol that ensures client-server communications on a network are secure. HTTPS makes use of the TLS to ensure sensitive data like passwords and credit card details are encrypted.

A03:2021 - Injection

Injection vulnerabilities are like giving someone the ability to run commands directly on your database, operating system, or application. It’s one of the oldest and most dangerous vulnerabilities, yet it still happens all the time. Maybe you’ve heard of Command Injection and SQL Injection somewhere. SQL injection is probably the most famous example. Let me show you something:

from django.db import connection

def get_user_by_username(username):

cursor = connection.cursor()

# User input directly concatenated into SQL query

query = f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '{username}'"

cursor.execute(query)

return cursor.fetchone()

Now this is extremely vulnerable to SQL injection. If an attacker passes ' OR '1'='1, it will become:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '' OR '1'='1'

and this returns ALL users (not good). Or an attacker could pass something even worse like '; DROP TABLE users; -- and completely wreck your database. The problem is that we are treating user input as trusted code, so never trust user input. We already talked about this a lot in the basic Python learning sessions.

Django’s ORM protects us from this like this:

from .models import User

def get_user_by_username(username):

return User.objects.filter(username=username).first()

# Even in raw SQL, use parameterization

def get_user_raw_secure(username):

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = %s", [username])

return cursor.fetchone()

Django automatically parameterizes this query:

return User.objects.filter(username=username).first(), Use %s placeholders to handle escaping here: cursor.execute("SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = %s", [username])

And it’s not just SQL injection. Command injection is equally dangerous:

import os

def ping_host(hostname):

# User input directly in shell command!

os.system(f'ping -c 4 {hostname}')

An attacker could pass something like, google.com; rm -rf /.

The secure way to handle this is by using subprocess with an argument list.

import subprocess

import shlex

def ping_host_secure(hostname):

# Validate input first

if not hostname.replace('.', '').replace('-', '').isalnum():

raise ValueError("Invalid hostname")

# Use argument list, not shell string

result = subprocess.run(

['ping', '-c', '4', hostname],

capture_output=True,

text=True,

timeout=10,

shell=False # << make it false when taking user input.

)

return result.stdout

So overall, don’t trust user inputs and never concatenate them directly into commands, queries, or code. Always use parameterized queries, proper escaping, or better yet, avoid executing dynamic code altogether.

Mitigations

- Parameterized Queries such as to use a prepared statements to separate code from data input

- Input Validation to validate and sanitize all user input at entry points

- Content Security Policy to Implement CSP headers to prevent XSS attacks

OWASP A04:2021 -> Insecure Design

This one is interesting because it’s not about a coding mistake, it’s about design flaws. It’s a design-level vulnerability. You can write perfectly secure code, but if your fundamental design is flawed, you are still vulnerable. This category addresses flaws in architecture and logic that occur before any code is written. Unlike implementation bugs, insecure design represents fundamental weaknesses in how systems are conceived and planned.

Why insecure!!

- Missing Threat Modeling: Lack of Security Controls Failure to identify and analyze potential security threats during the design phase.

- Lack of Security Controls: Failure to identify and analyze potential security threats during the design phase Absence of security mechanisms built into the system architecture from the start.

- Insufficient Risk Analysis: Not properly evaluating business logic vulnerabilities and attack surfaces.

For better understanding, here is a real world password reset feature (not secure):

from django.core.mail import send_mail

from .models import User

def request_password_reset(email):

try:

user = User.objects.get(email=email)

# Sending the actual password

send_mail(

'Password Reset',

f'Your password is: {user.password}',

'noreply@example.com',

[email]

)

return "Password sent to your email"

except User.DoesNotExist:

return "If that email exists, we sent reset instructions"

There are multiple design flaws here. First, passwords should never be retrievable, they should be hashed. Second, there is no rate limiting, so an attacker could spam password resets. Third, the system reveals whether an email exists in the database based on timing.

Suggested way of designing a password reset flow:

from django.core.mail import send_mail

from django.contrib.auth.tokens import default_token_generator

from django.utils.http import urlsafe_base64_encode

from django.utils.encoding import force_bytes

from django.core.cache import cache

from .models import User

import time

def request_password_reset(email, request_ip):

# rate limiting to prevent abuse

rate_limit_key = f'password_reset:{request_ip}'

attempts = cache.get(rate_limit_key, 0)

if attempts >= 3:

# always take the same time to respond

time.sleep(2)

return "If that email exists, we sent reset instructions"

cache.set(rate_limit_key, attempts + 1, 3600) # << 1 hour window

# Always respond the same way, don't leak email existence

try:

user = User.objects.get(email=email)

# Generate secure token

token = default_token_generator.make_token(user)

uid = urlsafe_base64_encode(force_bytes(user.pk))

# Send reset link, not password

reset_link = f"https://mywebsite.com/reset/{uid}/{token}/"

send_mail(

'Password Reset Request',

f'Click here to reset your password: {reset_link}\n\n'

f'This link expires in 1 hour.',

'noreply@example.com',

[email]

)

except User.DoesNotExist:

pass # Don't reveal that email doesn't exist

# always take the same time to respond

time.sleep(2)

return "If that email exists, we sent reset instructions"

This design incorporates several security principles: defense in depth, with multiple layers of protection; secure by default, with tokens that expire automatically; and fail securely, giving the same response regardless of whether the email exists.

Mitigation

- Conduct threat modeling early in the development lifecycle. Implement secure design patterns and embed security by design principles throughout the architecture process.

- Principle of Least Privilege - Each program or user should operate only with the least amount of privilege required to achieve their goals.

- Validation of Input - Every input from the user is validated to ensure it is in the expected format and reject it otherwise.

- Segregation of Tenants - Different environments such as live and test should be on separate networks and not share resources.

- Data must be encrypted at all times including during the resting phase.

- Fail Securely - Internal architectural details should be not be revealed in error messages.

- Running code should issue logs that reveal data such as type and volume of traffic as well as available bandwidth being used.

OWASP A05:2021 -> Security Misconfiguration

This rising threat highlights the critical importance of proper system configuration. This vulnerability stems from improper configuration of servers, databases, APIs, and other infrastructure components. Common issues include unnecessary features or services enabled by default, default credentials or settings left unchanged, unpatched systems running outdated software, overly permissive CORS policies, and verbose error messages revealing system details.

Attack Scenario The application server comes with sample applications not removed from the production server. These sample applications have known security flaws attackers use to compromise the server. Suppose one of these applications is the admin console, and default accounts were not changed. In that case, the attacker logs in with default passwords and takes over. Databases and applications typically come with default accounts making it easy for developers to get started quickly but must be disabled in the production phase.

Sometimes, or you could say many times, developers forget to change the default credentials during public deployment. For example, the settings.py file, which also contains sensitive data such as:

DEBUG = True # << Noo! never in production!

SECRET_KEY = 'django-l34rn1ng-123456' # << its hardcoded!

ALLOWED_HOSTS = ['*'] # << Allows any host - prone to host header attacks

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': 'mydb',

'USER': 'postgres',

'PASSWORD': 'password123', # hardcoded password

'HOST': 'localhost',

}

}

# No security headers

SECURE_BROWSER_XSS_FILTER = False

SECURE_CONTENT_TYPE_NOSNIFF = False

X_FRAME_OPTIONS = 'DENY' # good practice to deny it.

# Weak session settings

SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE = False # Sends cookies over HTTP

SESSION_COOKIE_HTTPONLY = False # Accessible via JavaScript

We set DEBUG = True when we are in the testing phase to better understand the errors we are facing, but if we leave this as “True” in a public environment, it reveals a lot of data about our application. Hardcoding secrets, passwords, and API keys is bad practice. Every single one of these settings is a security risk. Next, we can properly configure the production settings file, and it should look like this:

import os

from decouple import config

DEBUG = False

# secret key from environment

SECRET_KEY = config('SECRET_KEY')

# Specific allowed hosts

ALLOWED_HOSTS = ['0xzalzala.com', 'www.stackoverflow.com']

# secure database configuration

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.postgresql',

'NAME': config('DB_NAME'),

'USER': config('DB_USER'),

'PASSWORD': config('DB_PASSWORD'),

'HOST': config('DB_HOST'),

'PORT': config('DB_PORT', default='5432'),

'OPTIONS': {

'sslmode': 'require', # Require SSL for database connections

}

}

}

# Security headers and HTTPS enforcement

SECURE_SSL_REDIRECT = True # Redirect all HTTP to HTTPS

SECURE_PROXY_SSL_HEADER = ('HTTP_X_FORWARDED_PROTO', 'https')

SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE = True # Only send cookies over HTTPS

CSRF_COOKIE_SECURE = True

SECURE_BROWSER_XSS_FILTER = True

SECURE_CONTENT_TYPE_NOSNIFF = True

SECURE_HSTS_SECONDS = 31536000 # 1 year

SECURE_HSTS_INCLUDE_SUBDOMAINS = True

SECURE_HSTS_PRELOAD = True

X_FRAME_OPTIONS = 'DENY'

# Secure session settings

SESSION_COOKIE_HTTPONLY = True # Prevent JavaScript access

SESSION_COOKIE_SAMESITE = 'Strict' # CSRF protection

SESSION_COOKIE_AGE = 3600 # 1 hour timeout

# Content Security Policy

CSP_DEFAULT_SRC = ("'self'",)

CSP_SCRIPT_SRC = ("'self'",)

CSP_STYLE_SRC = ("'self'", "'unsafe-inline'")

The principle here is secure by default. Every setting should be as restrictive as possible, and you should only loosen them when absolutely necessary, with a clear understanding of the security implications.

Mitigations

- Client-side error reporting should be turned off

- Use of HTTPS should be enforced.

- All development tools like interactive consoles or debugging tools should be disabled.

- When working with a team, access to production data should be restricted to internal networks or require use of two factor authentication

OWASP A06:2021 -> Vulnerable and Outdated Components

Most modern software is developed using pre-built code in libraries and frameworks written by other developers. Such pre-built code might have vulnerabilities or, even worse, may contain code written with malicious intent.

- Log4j - This vulnerability allowed attackers to perform remote code execution by exploiting insecure JNDI (Java Naming & Directory Interface) lookups in the library.

- “Heartbleed” - Back in 2014, this vulnerability in OpenSSL cryptographic software allowed attackers to read large chunks of memory on the server.

- Solar Winds Attack - Attackers planted malware on the Orion software used by thousands of companies.

This rarely happens, but yes, it is possible. If you are using libraries written by someone else and import them into your real-world application, blindly running and installing the dependencies listed in the requirements.txt file can be risky. If a requirements.txt file looks like this with no version mentioned (not good):

Django

requests

pillow

celery

This can be dangerous because you don’t know exactly which versions you are using, and pip install might grab different versions, and maybe the version pip grabs is vulnerable and outdated. So the best practice is to always verify and use the exact safe version before installing and using it in your future production-ready application, such as (good practice):

Django==4.2.7

requests==2.31.0

Pillow==10.1.0

This is not the final solution. You still need to be up to date and be aware of daily cyber threats, attacks, new vulnerabilities, and regular updates.

Mitigations

- All unused dependencies, unnecessary features, components and files should be removed.

- Only obtain components from official sources over secure links preferably those with signed packages.

- Use dedicated tools to scan your dependency tree for security risks e.g Github security alerts and Shift Left.

- Monitor security bulletins.

- Perform regular code reviews & pen testing.

OWASP A07:2021 -> Identification and Authentication Failures

Application functions related to authentication and session management are often implemented incorrectly, allowing attackers to compromise passwords or session tokens and exploit other implementation flaws to assume other users’ identities temporarily or permanently.

Attack Scenario An attacker harvests a list of usernames for a website and then uses brute force attacks to try and guess the password for each username. Authentication Weaknesses can be caused by, permits default or weak passwords, Permits brute force attacks, Uses weak or ineffective credential recovery and forgot-password processes, such as “knowledge-based answers”, Uses plain text, encrypted, or weakly hashed passwords data stores or Has missing or ineffective multi-factor authentication. An attacker could either harvest usernames or try logging in (brute force attack) by using different types of usernames to see if the web server can confirm the existence of such usernames. Also password reset pages could be exploited to reveal the existence of registered email addresses.

Authentication is hard to get right, and the consequences of getting it wrong are severe. I have seen everything from authentication bypasses to session hijacking, and it all comes down to not properly verifying who users are and maintaining that verification throughout their session.

Let me show you a custom authentication implementation:

from django.http import JsonResponse

from .models import User

import hashlib

def login_view(request):

username = request.POST.get('username')

password = request.POST.get('password')

# plain text password comparison!

try:

user = User.objects.get(username=username, password=password)

# setting user ID in session without proper authentication

request.session['user_id'] = user.id

return JsonResponse({'status': 'success'})

except User.DoesNotExist:

return JsonResponse({'status': 'failed'})

This code has multiple critical flaws, such as plain text password storage, no rate limiting which allows brute force attacks, timing attacks where different response times reveal if a username exists, and improper session management.

We can improve this Django code using decorators and other methods like this:

from django.contrib.auth import authenticate, login

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

from django.views.decorators.csrf import csrf_protect

from django.views.decorators.cache import never_cache

from django.http import JsonResponse

from django.core.cache import cache

import time

@csrf_protect

@never_cache

def login_view(request):

if request.method != 'POST':

return JsonResponse({'error': 'Method not allowed'}, status=405)

username = request.POST.get('username', '').strip()

password = request.POST.get('password', '')

# Rate limiting based on IP

ip_address = request.META.get('REMOTE_ADDR')

rate_limit_key = f'login_attempts:{ip_address}'

attempts = cache.get(rate_limit_key, 0)

if attempts >= 5:

return JsonResponse({

'error': 'Too many login attempts. Try again in 15 minutes.'

}, status=429)

# Use Django's built-in authentication

user = authenticate(request, username=username, password=password)

# Always take the same time to respond (prevent timing attacks)

time.sleep(0.5)

if user is not None:

if user.is_active:

# Proper session management

login(request, user)

# Reset rate limit on successful login

cache.delete(rate_limit_key)

# Regenerate session key to prevent fixation

request.session.cycle_key()

return JsonResponse({

'status': 'success',

'redirect': '/dashboard/'

})

else:

return JsonResponse({

'error': 'Account is disabled'

}, status=403)

else:

# Increment failed attempts

cache.set(rate_limit_key, attempts + 1, 900) # 15 minutes

return JsonResponse({

'error': 'Invalid credentials'

}, status=401)

Session management is also important to consider review it as well in setting.py file:

SESSION_ENGINE = 'django.contrib.sessions.backends.db'

SESSION_COOKIE_AGE = 3600 # 1 hour

SESSION_SAVE_EVERY_REQUEST = True # Refresh session on activity

SESSION_COOKIE_HTTPONLY = True # Prevent JavaScript access

SESSION_COOKIE_SECURE = True # HTTPS only

SESSION_COOKIE_SAMESITE = 'Strict' # CSRF protection

# Middleware to handle session security

class SessionSecurityMiddleware:

def __init__(self, get_response):

self.get_response = get_response

def __call__(self, request):

if request.user.is_authenticated:

# Check for session hijacking indicators

session_ip = request.session.get('ip_address')

current_ip = request.META.get('REMOTE_ADDR')

if session_ip and session_ip != current_ip:

# IP changed - potential session hijacking

logout(request)

return JsonResponse({

'error': 'Session security violation'

}, status=401)

# Store IP for next check

request.session['ip_address'] = current_ip

response = self.get_response(request)

return response

For sensitive operations, implement multi-factor authentication:

# Two-Factor Authentication example

import pyotp

from django.contrib.auth.decorators import login_required

@login_required

def setup_2fa(request):

# Generate secret key for the user

if not request.user.totp_secret:

secret = pyotp.random_base32()

request.user.totp_secret = secret

request.user.save()

# Generate QR code for authenticator apps

totp_uri = pyotp.totp.TOTP(request.user.totp_secret).provisioning_uri(

name=request.user.email,

issuer_name='MyBanking App'

)

return JsonResponse({'totp_uri': totp_uri})

def verify_2fa(request):

token = request.POST.get('token')

user = request.user

if not user.totp_secret:

return JsonResponse({'error': 'MFA not set up'}, status=400)

totp = pyotp.TOTP(user.totp_secret)

if totp.verify(token, valid_window=1):

request.session['mfa_verified'] = True

return JsonResponse({'status': 'success'})

else:

return JsonResponse({'error': 'Invalid token'}, status=401)

Django provides a lot of prebuilt tools to implement proper session management, add rate limiting, and consider multi-factor authentication for sensitive applications.

Mitigations

- Enforce the use of strong passwords.

- Time outs after 5 failed login attempts

- Generic messages should be displayed after each attempt to login or reset passwords. Either the username or password is incorrect. If the email address someone@gmail.com exists on this website, a password reset link will be sent to it.

- Use two or multi factor authentication and do not ship or deploy with default credentials

A08:2021 - Software and Data Integrity Failures

This category focuses on making assumptions related to software updates, critical data, and CI/CD pipelines without verifying integrity. Many applications now include auto-update functionality, where updates are downloaded without sufficient integrity verification and applied to the previously trusted application. This vulnerability is about ensuring that the code you are running and the data you are processing has not been tampered with. One of the most common examples I see is insecure deserialization, which can lead to remote code execution.

Mitigations

- Use digital signatures to verify that software or data is from the expected source and has not been altered. Ensure you are downloading dependencies from trusted sources and verifying them.

- Software supply chain security tools, such as OWASP Dependency Check, should be used to verify that components do not contain vulnerabilities.

- Ensure there is a review process for code and configuration changes to minimize the chance that malicious code can be introduced into the software pipeline.

- Ensure that unencrypted data is not sent to untrusted clients without some form of integrity check to prevent the risk of them tampering with the data.

OWASP A09:2021 -> Security Logging and Monitoring Failures

As we implement a defense system, we also need logging and monitoring happening behind the application. This will make us aware in case any attack happens to our web application.

Attack Scenario A well known airline had a data breach involving more than ten years worth of personal data of millions of passengers, including passport and credit card data. The data breach occurred at a third-party cloud hosting provider, who notified the airline of the breach after some time. Insufficient Monitoring can be caused by auditable events like logins and transactions are not logged, Warnings and errors generate no or unclear log messages Response escalation processes are not in place or effective, Application cannot detect, escalate or alert for active attacks in real-time.

Here I am not giving you a code example anymore because the blog would become too lengthy and boring to read. So, just giving you a short overview: sometimes in code we don’t save logs of successful or failed attempts. In case someone is trying to brute force accounts, you would have no idea what’s happening. We need to implement proper security logging and monitor everything in our code. But sometimes we need to be careful not to log everything, such as passwords and Personally Identifiable Information (PII). It’s a bad practice to store logs of this. Instead, we can log just the username, and if taking card details, logging the last 4 digits is enough. So overall, log everything you need to detect and respond to security incidents, but never log sensitive data like passwords, full credit card numbers, or personally identifiable information.

Mitigation

- Ensure all login, access control, and server side input validation failures can be logged with sufficient user context to identify suspicious or malicious accounts.

- All old logs should be kept for an extended period for delayed forensic analysis and investigations.

- All high-value transactions must have an audit trail with integrity controls to prevent tampering or deletion.

- Effective incident response, response escalation and recovery plans must be established

OWASP A10:2021 -> Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF)

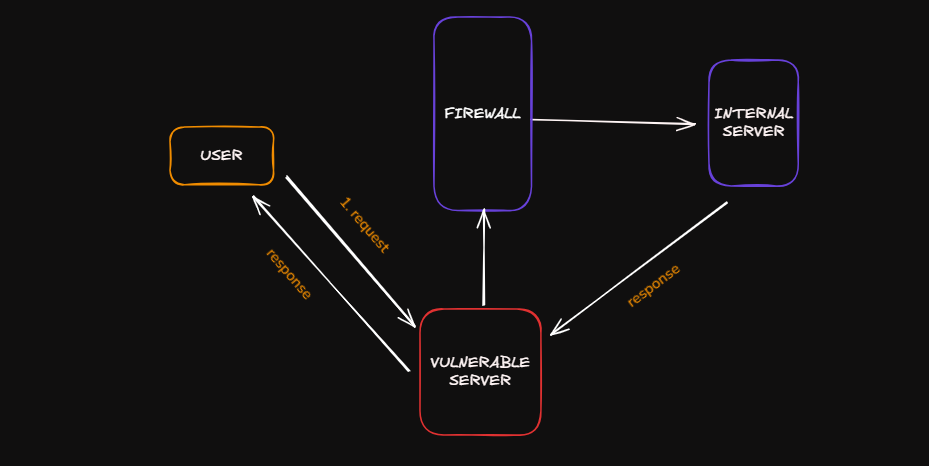

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) flaws occur when a web application fetches a remote resource without validating the user‑supplied URL. Web applications can trigger requests between HTTP servers to fetch remote resources such as software updates or to import metadata. It is used to gain access to sensitive internal data and can also be used to launch DDoS attacks. SSRF exploits could even be used to attack a third‑party website by using the vulnerable server. By spamming the vulnerable server with requests to fetch metadata from a third‑party website, the attacker can overwhelm that site while hiding behind the vulnerable web server.

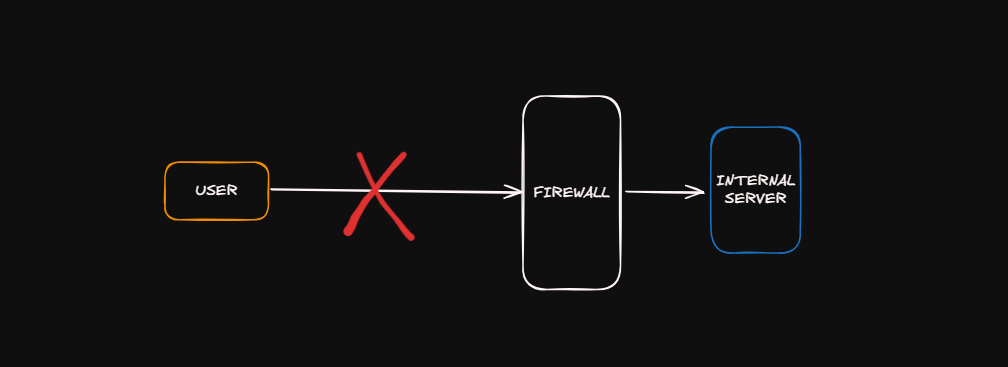

If an attacker sends a direct request to the internal server, then this will happen:

But it is possible if the third‑party server is vulnerable:

If we code a URL preview feature, it shouldn’t blindly fetch any URL the user provides. An attacker could use this to access internal services, such as an admin panel, scan internal networks, or access other local files. To protect against SSRF vulnerabilities, Django provides a good built-in SSRF protection tool.

If we code a URL preview feature, it shouldn’t blindly fetch any URL the user provides. An attacker could use this to access internal services, such as an admin panel, scan internal networks, or access other local files. To protect against SSRF vulnerabilities, Django provides a good built-in SSRF protection tool.

In general, SSRF vulnerabilities are fascinating and dangerous. They occur when your server makes requests to resources based on user input, potentially accessing internal systems that should not be reachable from the internet. The principle here is never trust user input, especially when it comes to URLs or network resources. Always validate, use allow lists when possible, and isolate services that make external requests.

Mitigations

- Enforce “deny by default” firewall policies or network access control rules to block all but essential intranet traffic.

- Segment remote resource access functionality in separate networks to reduce the impact of SSRF

- Sanitize and validate all user input data

- Disable HTTP redirections

- Disable raw responses to clients

- Only Make Outgoing HTTP Calls On Behalf of Real Users and limit the number of links a user can share in a given time frame.

Some Basic and Recommended Coding Principles!!

Now that we have covered all the OWASP Top 10 with some practical code examples as well, let us talk about the fundamental principles that underpin all of these vulnerabilities, which we have to keep in mind whenever writing code.

Serious input validation means no trust on outside data of your application, whether it’s from a user, another system, or a database; in all these cases it should be validated and sanitized. Output encoding means data needs to be encoded differently depending on where it’s being displayed. Give least privileges to users, whether normal users, database users, file permissions, or any kind of user roles; we need to give minimum privileges and what is necessary. We need to think of defense in depth. Not relying on a single security control, such as a firewall, we need to implement multiple security layers, such as hardware, software, and network layers. We need to handle exceptions safely and we should not reveal sensitive information or code.

Whenever writing code, make a checklist of all these things and make sure to keep it up to date in the future. We can create a checklist such as Authentication and Authorization level. This means all endpoints have authentication checks, authorization is checked at the object level, not just the endpoint level, session timeout is configured properly, MFA is enabled, and password flows should be done in a secure way, etc.

Next, Data Protection, such as all sensitive data should be encrypted whether at rest or in transit, HTTPS should be enforced everywhere, database passwords or configuration settings should be stored in environment variables, and sensitive data should not be logged.

Next, Input Validation, such as validating all user input, file upload restrictions and size, URL parameters should be validated, etc.

Next, Security Headers, make sure CSP is configured properly, HSTS enabled, X-Frame-Options set, X-Content-Type-Options set.

Dependencies should be up to date, with no known vulnerabilities, or you can match the hashes as well for integrity.

Next, Logging and Monitoring, we need to monitor and log security events, monitor alerts, etc.

Last but not least, Configurations. In OWASP 2025, the “MisConfiguration” vulnerability moved from rank #5 to #2. This means proper configurations should be taken more seriously and implemented. Small examples include what we saw in Django code when we were running a local server: we turned on Debug=True to see errors clearly, but you should not leave this True in production. It should be False. You should configure properly which hosts, systems, or networks are allowed to access, ensure proper SSL is configured on databases, and avoid hardcoded passwords, etc.

What Next??

Alright, we have covered a lot in today’s post and covered almost all the important conceptual points, as well as seen some real-world code implementations with OWASP Top 10 and the fundamental principles of writing secure code. Finally, we are so close to ending this journey. From next week onward, we will be implementing OWASP Top 10 in a real-world web application. We will be reviewing a vulnerable web application written in Django, in which you will see all the OWASP Top 10 vulnerabilities. We will not be limited to just viewing; we will improve the code from insecure to secure. There will be a lot of fun because you will be working on real-world application code review. I am really excited for the next remaining part of our series. So be ready and stay tuned till next week. If you have any questions, suggestions, improvements, or see any misinformation in the blog, please feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aziz-u000/

Recommended Resources to visit:

- OWASP Top 10: https://owasp.org/Top10/

- Django Security Documentation: https://docs.djangoproject.com/en/stable/topics/security/

- Python Security Best Practices: https://python.readthedocs.io/en/latest/library/security.html