Everyone, welcome back to Week 5 of our Secure Coding Series in Python. Last week, we focused on modular programming and error handling. We practiced it hands-on and applied those learning in our final mini project. This week, we are moving to our next topic, which is File Handling in Python. We will explore the world of file handling in Python. Working with files is a fundamental aspect of programming, and Python provides a rich set of tools for reading from and writing to various types of files. We will dive deep into file operations, such as reading and writing to a file, with exercises and code examples to master it. Let’s start.

File Handling or File I/O!!

File handling, also known as File I/O (input/output), in the context of computer programming, refers to the ability to work with files. Files can store a wide range of data, they can be text documents or binary files. File handling in Python allows you to perform various operations on these files, such as reading, writing, deleting, and even modifying their contents. Programs often need to read configuration files to know how they should run, save logs in a file, store results, or read data from files, for example, filtering spam messages that the program reads from a file.

This is essential when dealing with data persistence, configuration files, log files, and more. Python offers several ways to work with files, including basic operations like opening, closing, reading, deleting, and writing in different formats. Whether a file is uploaded by a user or created through a program, handling files the right way is very important. Why? Because if we don’t handle it correctly, an attacker can exploit them and upload or generate dangerous files, which can lead to serious security risks.

So we are going to slow down and focus on how to handle files in the best way. We will walk through the best practices for opening, reading, and writing files in Python. For now, we are not focusing on writing GUI based programs to process files. Instead, we will learn the core concepts of how things work. You will also learn how to keep your code safe, efficient, and clean so you don’t run into those sneaky bugs that attackers love. By the time we finish this week, you will understand another important aspect of writing secure code. So stay focused, do your best to understand the concepts, and never stop exploring more. Let’s dive in and start exploring file handling in Python together.

There are two types of files that are very important to understand before working with files in Python:

- Binary files: In simple words, binary files are non-text files such as images (.jpg, .png), videos (.mp4, .mov), executable files, etc.

- Text files: Text files contain readable text such as plain text, .CSV, .JSON, .DOCX, .LOG, etc.

We will try to understand all of these and learn how to work with them. Don’t worry, I will make sure to present everything in an easy to understand way with practical code examples as well.

Opening, Closing, Reading, and Writing Text Files

In the file handling process, you must work on opening and closing files. Before you can read or write to a file, you must open it. Python provides the open() function for this purpose.

The open() function takes two parameters. The file path and the mode in which you want to open the file. We can specify the modes as follows: "r" means read mode, "w" means write mode (which overwrites existing content or creates the file if it doesn’t exist), and "a" means append mode (which adds to the end without deleting old content).

The mode specifies the file’s intended use, whether you are reading, writing, or both. There are several modes available, including:

r: Refers to Read (default mode). It opens the file for reading. If you don’t specify the mode, Python will take the read mode as default.w: Refers to Write. It opens the file for writing, truncating the file if it already exists or creating a new file if it does not exist.a: Refers to Append. It opens the file for writing, preserving the existing content, and appends to the end of the file or creates a new file if it does not exist.b: Refers to Binary. It addsbto any mode to open the file in binary mode. For example,rbopens the file for reading in binary mode, andwbopens the file for writing in binary mode.

There are other modes as well, such as r+, w+, and a+, which you can explore, but for now, we are focusing on the basic modes.

Reading a File in Python!!

Suppose we already have a file in our system. The method to read the content from a file needs the file path, which can be a relative or absolute path, and then the access mode "r", such as:

# opening a file for reading

f = open("courses.txt", 'r')

Above, f means the file opened with the open() function, where we have the file name and access mode inside. Now, to read the content from a file:

# reading and printing the file content

content = f.read()

print(content)

After you are done with a file, it is essential to close it using the close() method. Closing the file releases any system resources associated with it and ensures that the changes you made to the file are saved properly, as shown below:

# Closing the file

f.close()

Now, to make it work together, it looks like this:

# opening a file for reading

f = open("courses.txt", 'r')

# reading and printing the file content

content = f.read()

print(content)

# Closing the file

f.close()

We can also store the text file name in a variable, such as file_path:

file_path = "courses.txt"

f = open(file_path, 'r')

content = f.read()

print(content)

f.close()

To explain the above code. First we specify the file path. The file path can be defined using an absolute path (/home/user/folder/filename.txt) or a relative path (filename.txt). In our case, the file is in the same directory, so I am using the relative path. Next, we use the open() function and provide two arguments. The first one is the file path, and the second is the access mode, which in our case is 'r', meaning read mode. So, we are reading the file content. Closing the file is very important, and this can be done using the close() function.

While manually opening and closing files is a common practice, Python offers a more convenient and safer way to work with files. The with statement ensures that the file is properly closed after it is used, even if an exception is raised during the program’s execution. This eliminates the need to explicitly call close(), so you don’t need to manually close the file.

Here is how the with statement is used:

with open('courses.txt', 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

Now, to print the content of the file using the print() function, it looks like this:

with open("courses.txt", 'r') as f:

content = f.read()

print(content)

In the above code, we open the file courses.txt in read mode and read its entire content using the read() method. The content is then stored in the content variable and printed using the print() function.

The file is automatically closed after leaving the with block. The with statement provides a cleaner and more readable way to work with files, and it is the recommended approach in most situations. You don’t need to close the file manually, the with statement will handle it for you.

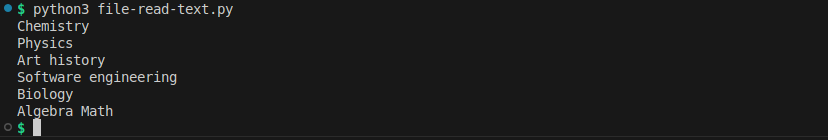

Write and save this code in a Python file named file-read-text.py in VS Code, and then run it. Also, create and save some text in a .txt file that contains some content, such as subject names, so that we can read that file’s content.

Output:

Note: If you face a FileNotFoundError while running the above program, but you are completely sure that you have created the file and the file name is correct and available in the path, then please make sure you have opened the code editor in the same directory.

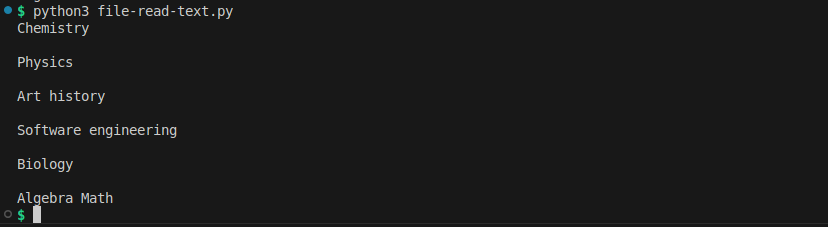

Reading Line by Line

Reading an entire text file at once can be memory-intensive, especially for large files. Python allows you to read files line by line using a for loop. This approach is more memory-efficient.

with open('courses.txt', 'r') as f:

for line in f:

print(line)

In this code, we open the file courses.txt and iterate through it line by line, printing each line as we go.

Output:

Or we can do it using the readline() method to print or read the file content line by line:

with open('courses.txt', 'r') as f:

first_line = f.readline()

print(first_line)

second_line = f.readline()

print(second_line)

third_line = f.readline()

print(third_line)

Note: You can name the alias anything. I used as f:, but you can name it something else, such as as file:.

Output:

Writing to a File in Python!!

Writing data to files is just as essential as reading from them. In this section, we will explore various techniques for writing to files. We will also discuss how to append data to existing files.

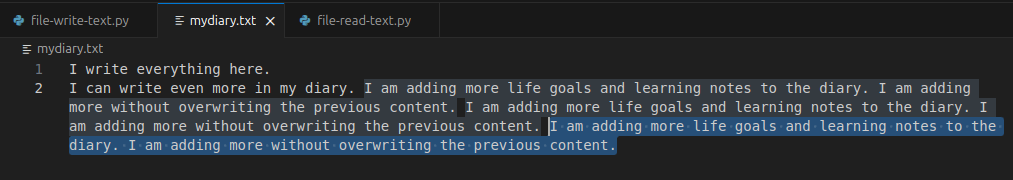

Writing Text Files

Writing to text files is a fundamental aspect of file handling in Python. You can create, open, and write data to text files with ease. To write to a text file, you need to open it in write mode (w). Here is an example:

with open('mydiary.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write('I write everything here.\n')

f.write('I can write even more in my diary.')

In this code, we open a file called mydiary.txt in write mode (w) and use the write() method to add content to the file. We include a newline character (\n) to indicate the start of a new line. You can add even more text as well. However, if you open the file again and write more text, it will overwrite the existing information in the file. If you don’t want to overwrite the content, we have another method for this, which is appending to a file.

Appending to Files

Sometimes, you may want to add data to an existing text file without overwriting its current content. You can do this by opening the file in append mode (a). In this mode, you are writing to the file while keeping the previous content intact.

with open('mydiary.txt', 'a') as f:

f.write(" I am adding more life goals and learning notes to the diary.")

with open('mydiary.txt', 'a') as f:

f.write(" I am adding more without overwriting the previous content.")

In this example, the file mydiary.txt is opened in append mode, and the write() method is used to add new content to the end of the file without affecting the existing data. Additionally, it is recommended to use append mode when you don’t want to replace your previously saved data.

Output:

Working with Binary Files!!

Working with binary files in Python involves reading and writing data in its raw binary format. Binary files can store any type of data, including images, audio, video, or any other non-text information.

Reading Binary Files

Binary files, like images or executable, require a different approach to reading compared to text files. In this section, we will see how to read binary files. To read a binary file, open it in binary reading mode (rb) and use the read() method to obtain its contents.

with open('image.jpg', 'rb') as f:

content = f.read()

print(content) # or do anything else to the binary file

Write and save this code in a Python file named file-read-bin.py in VS Code, and then run it.

Binary files can be more challenging to work with because they may contain various data types, and interpreting them correctly is crucial. Additionally, if you want to work with image manipulation, Python’s Imaging Library (PIL) is great, but for now, we are just focusing on understanding how to handle binary files in Python.

Writing Binary Files

Writing to binary files is crucial when working with non-textual data like images, audio, or other binary file formats. To write to a binary file, open it in binary writing mode (wb) and use the write() method to add binary data.

#Opening a binary file for writing

with open('scanner.exe', 'wb') as f:

#Writing binary data

content = f.write(b"Document Scanner tool")

We used the same approach as we did above with text files, but the only difference is the reading and writing mode. Additionally, in real-world programming, we don’t usually write to .exe files like the example shown here, it’s just for demonstration purposes.

Deleting a File

To delete any file, we can use the os module. We already discussed modules and modular programming in detail in our previous post, but in simple words, we import another Python file written by someone else, which contains functions, often related to operating system tasks. The os module includes several useful functions, and in our case, we will use the remove() function from the os module to delete any kind of file. Let’s understand it practically:

import os

os.remove("scanner.exe")

Above, we use import to bring in the os module, and then we use the remove() function as os.remove(). Inside the function, we provide the filename in double quotes.

To summarize the concept of reading and writing to a file in Python: the first step is opening a file, which is done with the open() function. This function takes at least two parameters, the file path and the access mode.

Once the file is opened, you can read it in a few different ways:

.read()reads the whole file into a single string (or a specified number of characters if an argument is given)..readline()reads one line at a time..readlines()reads all lines into a list, where each element represents one line (including the newline character).

For writing, Python offers .write() to add a single string and .writelines() if you already have a list of strings you want to write one after another. Appending works just like writing, but you use "a" mode instead of "w" so that you don’t overwrite the existing contents. For example, you can first write several lines, then open the file in append mode to add a line like "Hey, I am adding some new content.\n", and finally reopen or inspect the file to see that the earlier contents remain.

Finally, closing the file is very important. After finishing reading or writing, you call close() on the file object so that Python frees up system resources. However, instead of using close(), we can use the with statement, which automatically handles closing the file by default.

Now it’s time to practice more, but this time, we will work with CSV and JSON files. The handling process is completely the same as with text files, but this time I will introduce some basic modules that are very useful when working with structured files such as CSV and JSON.

Working with CSV Files

CSV (Comma Separated Values) files are one of the simplest and most common ways to store tabular data. They organize information into rows and columns, separated by commas, and are often used for exporting or importing data between spreadsheets, databases, or even web applications. You can easily open and edit CSV files with tools like Excel or Google Sheets, but working with them programmatically in Python gives you much more control.

Reading CSV

To work with CSV files in Python, we use the csv module, which is specially designed for reading and writing CSV data properly. We can also use split(',') to break lines apart, and yes, that would technically work, but it quickly fails when your data has commas inside quotes or special characters. That’s why using the csv module is the correct and reliable way.

import csv

with open('subscribers.csv', 'r') as f:

reader = csv.reader(f)

for row in reader:

print(row)

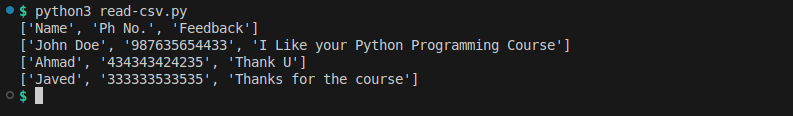

Output:

In this example, we imported a module

In this example, we imported a module csv and we open a file called subscribers.csv in read mode and pass it into csv.reader(), which reads the file line by line and automatically separates the data into lists. Each list represents a single row in the file. The for loop then prints each row one by one so we can see how the data looks. You will notice that the csv module handles quoted text, numbers, and even missing values without any issue. This makes it far more reliable than trying to split strings manually.

Writing CSV

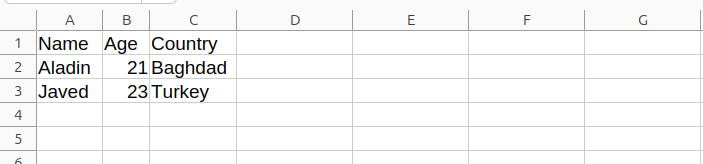

Now, let’s look at how to write data into a CSV file. For this, we use csv.writer(). Just like reading, it takes care of everything for you, putting commas in the right places, handling quotes, and ensuring each list you provide becomes a proper row in the file.

import csv

data = [

['Name', 'Age', 'Country'],

['Aladin', '21', 'Baghdad'],

['Javed', '23', 'Turkey']

]

with open('subscribers-list2.csv', 'w', newline='') as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerows(data)

Here we created a list of lists called data, where each inner list represents a row. We open a file named subscribers-list2.csv in write mode and pass it to the writer. Then writer.writerows(data) writes all rows to the file in one go. The newline='' argument is important because, especially on Windows, it prevents extra blank lines from appearing between rows.

When this code runs, it overwrites any existing file with the same name and saves all the data in proper CSV format (you can use append mode if you don’t want to overwrite). After running it, you can open the file in Excel or any text editor to verify that the data is stored cleanly in columns.

Output:

Working with JSON files

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is another popular way to store and share data, especially structured data. It’s very readable for humans and easy for machines to parse, which is why it’s widely used for configuration files, APIs, and even application settings. The format looks like a combination of Python dictionaries and lists, and Python’s built-in json module makes it simple to work with.

Writing JSON

When you need to store data like user information, settings, or API responses, you can write it into a JSON file. Here is how:

import json

data = {

"username": "Javed",

"password": "1amp00r1122",

"role": "Help Desk Engr",

"is_employee": True

}

with open('employees.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(data, f, indent=2)

In this code, we created a Python dictionary named data that contains key-value pairs. Each key represents a field (like username, password, or role), and its value can be a string, number, boolean, list, or even another dictionary. We then open a file named employees.json in write mode and use json.dump() to convert our dictionary into JSON format and write it directly into the file. The indent=2 just makes the output look nice and easy to read by adding spaces for indentation.

After running this, you will see a file called employees.json created in your directory. You can open it in any text editor to see the data stored in clean JSON format.

Output:

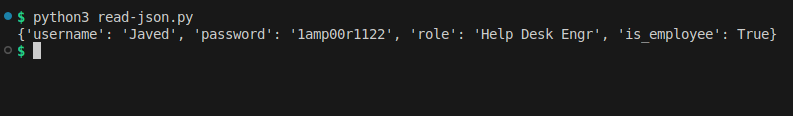

Reading JSON

Now let’s see how to read data back from a JSON file.

import json

with open('employees.json', 'r') as f:

employees = json.load(f)

print(employees)

This time we use json.load() to read and convert the JSON data from the file back into a Python dictionary. Once loaded, you can access its values the same way you would with any dictionary. For example, employees["username"] would return "Javed".

Output:

However, when dealing with external files, it’s a good idea to prepare for errors. If the file doesn’t exist or the JSON is malformed (maybe someone manually edited it and broke the syntax), your program could crash. That’s where a simple try and except block helps.

import json

try:

with open('config.json', 'r') as f:

config = json.load(f)

except FileNotFoundError:

print("The file is missing!")

config = {}

except json.JSONDecodeError:

print("Config corrupted!")

config = {}

Here we are telling Python to try reading config.json. If the file is missing, it prints a file not found message, so your program keeps running. Similarly, if the file exists but contains invalid JSON, it catches the decoding error and still prevents a crash.

Output:

Working with JSON files is an essential skill because most web services and applications communicate using JSON data. Whether you are saving user preferences, API responses, or configurations, the json module makes everything simple and reliable.

Handling file exceptions

Reading from files may raise exceptions if the file does not exist, cannot be opened, or is corrupt. Handling these exceptions is essential for reliable file operations. Working with files is not always smooth because a lot can go wrong. Maybe the file you are trying to read doesn’t exist, cannot be opened, or is corrupt. Or maybe you don’t have permission to access it, or the disk is full and your program can’t save anything. If you don’t handle these cases, your program will simply crash and show a messy traceback that looks confusing to users. That’s why it’s important to use exception handling with try and except.

For example, a bad practice would be just opening a file with f = open('topplayers.txt', 'r') and trying to read it, which will crash immediately if the file is not there. The better practice is to wrap your file-handling code inside a try block and handle specific exceptions like FileNotFoundError, IOError, or PermissionError, so your program doesn’t break. This way, if the file is missing, you can show a simple message like “File not found,” and if permission is denied, you can explain that clearly instead of confusing the user with random errors.

Using exception handling not only makes your program more stable but also more user friendly, because instead of failing unexpectedly, it simply explains what went wrong and keeps running. (We have already studied error handling in our previous week 4 blog, so check it out if you haven’t yet.) Below I am giving examples of handling exceptions when working with files.

try:

with open('topplayers.txt', 'r') as file:

content = file.read()

except FileNotFoundError:

print("File not found!")

except IOError as e:

print(f"An error occurred! Try Again: {e}")

In this example, we attempt to open a file that does not exist, which raises a FileNotFoundError. We catch this exception and provide an appropriate error message. We also catch the generic IOError to handle any other potential issues.

Output:

Keeping all above in mind and applying in our coding journey is not enough. Below I am giving some more good practices along comparison with bad practices of writing code whenever working with file in python. So you can get better idea.

1. Always Close Files!!

When you open a file in Python, the system gives it certain resources to work with, and if you forget to close that file, you risk wasting those resources or even ending up with incomplete writes where not all your data is saved properly. This is something many beginners overlook because their small programs seem to work fine at first, but in real projects it can lead to corrupted data, strange bugs, or even program crashes. The habit you want to build is to always close your files, and while you can do it manually using close(), the smarter and recommended way in Python is to use the with open(...) as f: approach. This method automatically closes the file once the block of code is done, even if an error happens, so you don’t have to worry about forgetting. For example, the bad practice would look like f = open('example.txt', 'r') and then reading data without closing it, but the good practice is simply writing with open('example.txt', 'r') as f: and letting Python handle the closing for you.

Look at below 2 codes comparison, with good and bad practices.

Bad Practice:

f = open('example.txt', 'r')

data = f.read()

# File not closed!

Good Practice:

with open('example.txt', 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

with is a good, safe and recommended to use so it will handle by default.

2. Use Exception Handling!!

When you are working with files, things don’t always go as planned. Maybe the file is not there, maybe it’s locked, or maybe your program simply doesn’t have permission to open it. Without protection, these small issues can crash your entire script. Instead of assuming everything will go perfectly, you tell Python, “Try this, but if something goes wrong, handle it calmly.” This keeps your program alive.

Bad Practice:

f = open('customers.txt', 'r')

data = f.read()

If the file is missing, the program crashes with an ugly traceback.

Good Practice:

try:

with open('customers.txt', 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

except FileNotFoundError:

print("File not found.")

except PermissionError:

print("Permission denied.")

In this improved version, we use a try block to attempt reading the file safely. If the file is missing or access is blocked, the except blocks catch those specific problems and print simple, human-readable messages instead of confusing error dumps. This approach keeps your program running smoothly, gives useful feedback to the user, and shows that your code can handle real-world problems gracefully.

3. Use File Modes Properly!!

When you open a file in Python, you have to be very clear about what you want to do with it, because Python gives you different modes like r for reading, w for writing, and a for appending. Using the wrong one can cause serious problems, especially with w, because it doesn’t just open the file, it completely overwrites whatever was inside before, which means all your old data is gone in a second. For example, if you write with open('example.txt', 'w') as f: and add new content, everything that was previously in that file is erased, which can be very dangerous if that file had important information. If instead you just want to add something new without removing the old content, the safer option is to use append mode with a, like with open('example.txt', 'a') as f:, which will keep the existing content and simply add your new lines at the end. So double check the mode you are using and match it with your intention.

Bad Practice (it overwrites existing content):

with open('example.txt', 'w') as f:

f.write("New content")

Good Practice (append safely):

with open('example.txt', 'a') as f:

f.write("Additional content\n")

4. Handle Large Files Efficiently!!

Sometimes you might be working with really big files, maybe several gigabytes in size, and if you try to read the whole file at once using .read(), Python will attempt to load all of it into memory. This can slow down your computer, eat up all the memory, or even crash your system completely. The better way is to process the file in smaller chunks, usually line by line. For example, instead of data = f.read(), you can loop over the file with for line in f: and handle each line as you go. This method only keeps a small part of the file in memory at any time, which makes your program much more efficient and stable when working with large files. Below I mentioned some good and bad practices when working with large files.

Bad Practice:

with open('large_file.json', 'r') as f:

data = f.read()

Good Practice:

with open('large_file.json', 'r') as f:

for line in f:

process(line)

5. Use os and pathlib for File Paths

One of the easiest mistakes we make as a beginners is hardcoding file paths like "/home/soc-aziz/CODE/source-code/secure-coding/week5/file_handling.py". The problem with this approach is that it only works on your own system. If someone runs your code on Windows or Mac, that exact path won’t exist, and even the way slashes are used in file paths is different across operating systems. So to solve this issue, python provides os and pathlib module that handle paths in a way that works everywhere and no need to write fixed string, you can use Path.home() / 'CODE' / 'source-code' / 'secure-coding' / 'week5' / 'file_handling.py', which automatically builds the correct path for the user’s system, whether it’s Windows, Mac, or Linux. So the good habit is simple is do not hardcode your paths, leave it for python and it will handle with os and pathlib. Below I am mentioning the good and practices for file paths.

Bad Practice:

# in linux I am using this format

with open('/home/soc-aziz/CODE/source-code/secure-coding/week5/file_handling.py', 'r') as f:

Good Practice:

from pathlib import Path

file_path = Path.home() / 'CODE' / 'source-code' / 'secure-coding' / 'week5' / 'file_handling.py'

with file_path.open('r') as f:

data = f.read()

Now it is clean.

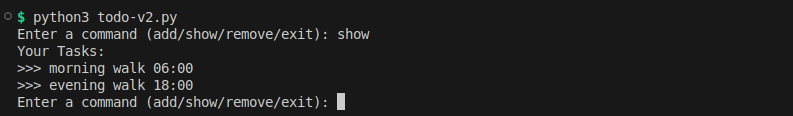

ToDo v2 - Mini Project

Back in Week 2, we built a simple to-do list program that stored all tasks in memory. It was straightforward and easy to understand. The program started with an empty list called tasks, and then it entered a while True loop that repeatedly asked the user to enter a command: add, show, remove, or exit. If the user chose to add a task, the program asked for the task description and appended it to the list, confirming with a friendly message saying “Task added.” When the user wanted to see all tasks, the program printed “Your Tasks:” and listed each task one by one with a dash in front for clarity. Removing a task worked similarly: the program asked which task to remove, checked if it existed in the list, removed it if it was found, and printed “Task removed,” or otherwise informed the user that the task was not found. and at the end, if the user typed “exit,” the program said Exit program and ended, and any unknown command prompted a polite message telling the user to try again.

This Week 2 version worked perfectly for learning the basics, but it had some limitations. Since everything was stored in memory, once the program closed, all tasks were lost. There was no way to save the tasks permanently, and there was also no error handling if something unexpected happened. If we wanted to make this program more practical, we would need to save tasks to a file, handle files safely, and make sure it works on any computer. Week 5 teaches us exactly how to do that. By applying Week 5 best practices, we can take this simple in-memory to-do list and turn it into a file-based program that is safe, portable, and user-friendly.

So now we are just updating our week 2 project todo.py to version 2 by applying Error and File handling. Here is the project code for our todo-v2.py program.

from pathlib import Path

#--file-path-for-storing-tasks

file_path = Path.home() / 'CODE' / 'source-code' / 'secure-coding' / 'week5' / 'tasks.txt'

#--Function-to-load-tasks-from-the-file

def load_tasks():

tasks = []

if file_path.exists():

try:

with file_path.open('r') as f:

tasks = f.read().splitlines()

except PermissionError:

print("Cannot read tasks: Permission denied.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred while reading tasks: {e}")

return tasks

#--Function-to-save-tasks-to-the-file

def save_tasks(tasks):

try:

with file_path.open('w') as f:

for task in tasks:

f.write(task + "\n")

except PermissionError:

print("Cannot save tasks: Permission denied.")

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred while saving tasks: {e}")

#--Load-tasks-when-the-program-starts

tasks = load_tasks()

#--Main-program-loop

while True:

try:

command = input("Enter a command (add/show/remove/exit): ").lower()

if not command.strip():

print("Empty input is not allowed.")

continue

if command == "add":

task = input("Enter a new task: ").strip()

if not task:

print("Empty Task Cannot be added")

continue

tasks.append(task)

save_tasks(tasks)

print("Task added.")

elif command == "show":

if tasks:

print("Your Tasks:")

for t in tasks:

print(">>>", t)

else:

print("No tasks found.")

elif command == "remove":

task = input("Task to remove: ")

if task in tasks:

tasks.remove(task)

save_tasks(tasks)

print("Task removed.")

else:

print("Task not found.")

elif command == "exit":

print("Exit Program.")

break

else:

print("Unknown command, try again.")

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n ^C Interrupted and Exiting")

break

Now let’s look at what we have updated! In Python, the pathlib module makes it easier to work with file and folder paths. When we write from pathlib import Path, we are importing the Path class, which lets us handle paths in a clean and modern way instead of just using plain strings. For example, writing long paths like "/home/soc-aziz/CODE/source-code/secure-coding/week5/file_handling.py", we can create a Path object that automatically understands whether we are on Windows, Linux, or Mac, and it uses the correct style of slashes. With Path, we can easily check if a file exists, create new folders, read and write files, or join paths together. This makes file handling in Python much simpler and more reliable.

Some improvements we made as compare to previous project:

- Tasks are now stored in a file using

pathlib, so they are saved even after the program closes. - It uses

with open(...)for reading and writing, which automatically closes the file and prevents resource leaks. - Exception handling is added for permission issues or unexpected errors, preventing the program from crashing.

- By using

Path.home()and building paths with/, the code is portable and works on Linux, Mac, and Windows without changes. - Additionally this time I have added more possible exceptions to handle it safely such as user cannot added empty value and this is done using

strip()method.

Now you will not lose your previous added or modified tasks. Below I already added 2 dummy tasks and then I closed the program then again I asked to show previous added tasks.

No matter if we close the

No matter if we close the todo-v2.py and then reopen it, we will still have access to the previously written data. This is because we wrote the code in such a way that it saves the record in a file. I think I have explained it in an easy way, so you should not face any issues. In case you do, please google google google your code errors, solve them, and try to break the code logic, rebuild it, and then break it again. That’s it.

Book Reading –> Chapter 3 (Mitigations)

In Chapter 3 of the book Designing Secure Software: A Guide for Developers by Kohnfelder, the author introduces the idea of mitigation. The main understanding here is that security should not only focus on fixing problems after they occur but also on lowering the chances of those problems happening in the first place. This is known as minimizing the attack surface, making sure that your program offers fewer paths for an attacker to exploit. For example, instead of allowing all possible user inputs and then trying to filter them later, it is better to limit what input you accept in the first place.

Another important idea is the principle of least privilege which means give the minimum permissions necessary. If a program only needs to read data, it should not also have the ability to write or modify it. This way, even if something goes wrong, the damage stays limited. Finally, Kohnfelder stresses the importance of failing in a safe way. When an error happens, the program should shut down gracefully or recover without exposing sensitive details or leaving the system vulnerable. Altogether, these practices show that good security is just as much about prevention and cautious design as it is about reacting to problems.

Thanks for reading! Stay tuned until next week.