Welcome back again to Week 4 of our Secure Coding Series in Python. Last week we learned about Python Functions along with Parameters, Arguments and how things works. Now we are moving to more interesting topics in our series which is Modular Programming and Error handling and will also touch some defensive coding approach as well. This post maybe a bit long and cover more topics but no worry I will try to explain things in well detail to make it easy for you to follow. let’s start.

Modular Programming in Python!!

Till now we were writing code in just one file, but as we move into complex programming, we need to write and organize code properly. We can do this with the help of organizing code into multiple files. When we split our code into separate files, this is called modules.

A module in Python is simply a file that contains Python code, such as functions, classes, or variables, which you can use in another program. You create a module just by saving your code in a .py file, and then you can import it into other files using the import keyword. For example, if you have a file named mathfunctions.py with some functions inside it, you can reuse those functions in another program by importing that module. Make sense? No worries, we will learn it practically later.

A Python library is basically a collection of modules, while a module is just a single Python file. This is helpful because we can use libraries that other developers have created, so there’s no need to write everything from scratch. For example, math, random, and datetime are built-in Python libraries, and you can also install and use third-party ones like numpy, pandas, or even your own custom-made libraries.

But when we import something like requests, it’s actually a library that contains multiple modules inside it, and when you import it, you’re usually importing the main module of that library.

Now let’s understand modular programming like this: suppose you are building a big Ecommerce app. Instead of writing everything in one file, you can create separate modules like products.py, customers.py, and orders.py. Each module handles its own part, and then you connect them together to the main Python file using the import keyword. This way, the code becomes neat, reusable, and easier to manage. This is called modular programming. We will also learn it practically with code examples later.

First, look at this simple example to understand the process and syntax of how to write and call your own functions. I have 2 files: myfunctions.py and main.py.

myfunctions.py contain the following code.

def message(name):

print(f"Hello {name}.This is my first module")

Save this file as myfunctions.py.

To explain the above code, we created a file called myfunctions.py, and inside it, we have one function defined with def message(). The text inside the function is printed using an f-string. The f tells Python that the string might contain placeholders inside curly braces {} that need to be evaluated. So {name} gets replaced with the value of the variable name.So overall, when we call this function from another Python main file, it will simply execute and print the functionality defined inside the function.

Our function is ready. Let’s call it from another file, which is main.py. Within our main.py file, we can import myfunctions as a module and then use the message(name) function. The code of main.py file looks like this:

import myfunctions

def main():

myfunctions.message("Learners")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

Save this code as main.py.

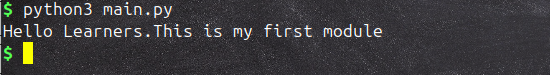

Output:

First, we use the

First, we use the import statement to bring in our own module (myfunctions) into the main.py file. Once imported, we can call any function defined in myfunctions.py. For example, the syntax to call a function from another file is module_name.function_name(). In our case, that would be myfunctions.message(). To make it simpler, we first write the module name, and then connect the function name using a dot (for instance, module_name.function_name()). So overall, it becomes myfunctions.message(). Also, notice that we only write the module name, not the .py extension, and after the dot, we add the function name.

The next line, if __name__ == '__main__':. In Python, every file has a built-in variable called __name__ that tells the interpreter how the file is being used. If you run a file directly (for example, by typing python main.py), Python sets __name__ to "__main__". But if that same file is imported into another script as a module, then __name__ is set to the module’s name. (For example, "myfunctions" -> module). This is why you often see and write the line if __name__ == '__main__': in Python code. It ensures that the file can act both as a standalone program and as a reusable module without executing unintended code when imported. it is a good practice to use.

In case you still have confusion about how this works, let’s take the unit converter mini project from Week 3 and put all the conversion functions in a separate file called conversions.py. Then we create another file called main.py. In the conversions.py file, we will define all the conversion functions, and in main.py we will call those functions from our main program. This way the code will look clean and organized. Look at the code below, try to understand it, and don’t worry, we will explain it more after the code.

conversions.py file contain the following functions:

def km_to_miles(km):

return km * 0.6

def miles_to_km(miles):

return miles / 0.6

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(c):

return (c * 9/5) + 32

def fahrenheit_to_celsius(f):

return (f - 32) * 5/9

Our conversions.py file, and all our functions are in a separated single python file.

here is our main.py file and we will also use import statement to import all the functionalities in the above code in our main python file

main.py

import conversions

while True:

print("\nUnit Converter")

print("1. Km to Miles")

print("2. Miles to Km")

print("3. Celsius to Fahrenheit")

print("4. Fahrenheit to Celsius")

print("5. Exit")

choice = input("Enter your choice: ")

if choice == "1":

km = float(input("Enter km: "))

print("In miles:", conversions.km_to_miles(km))

elif choice == "2":

miles = float(input("Enter miles: "))

print("In km:", conversions.miles_to_km(miles))

elif choice == "3":

c = float(input("Enter °C: "))

print("In °F:", conversions.celsius_to_fahrenheit(c))

elif choice == "4":

f = float(input("Enter °F: "))

print("In °C:", conversions.fahrenheit_to_celsius(f))

elif choice == "5":

print("Exit Program!")

break

else:

print("Invalid choice")

And this is our main.py file, which we will run to get the same result as we saw in the previous week’s mini project.

We can’t call those functions until we use import module_name as you can see above we did at the top of the code and then you can see conversions.km_to_miles(km), conversions.celsius_to_fahrenheit(c), conversions.fahrenheit_to_celsius(f) now look carefully name “conversions” is repeated because this is the module name and then dot and then function name. I have tried to explain the same above but now I hope it is very clear with the help of implementing it practically.

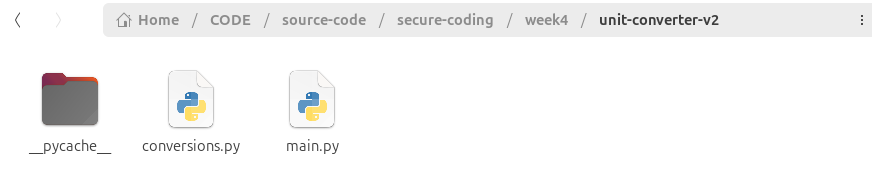

Now make sure to save the first code in the conversions.py file and save the second code in the main.py file. It will look like this, as you can see below:

Now, you don’t need to run both files, you only have to run the

Now, you don’t need to run both files, you only have to run the main.py file, and it will automatically use the code from conversions.py.

But how does this work behind the scene in python??

Let’s explain how Python import works in modular programming. When you use import, Python goes and looks for the module you mentioned. If it’s your own module (like conversions.py), Python searches in the same folder as your main program and loads the code from that file. This way, you can reuse the functions, classes, or variables from your own files just by importing them. Also when you import from public or built-in libraries (like math, random, or third-party ones like numpy), Python first checks its built-in library collection, and if it doesn’t find it there, it checks the libraries you installed using pip. These libraries are already made by other developers and can be used directly in your code. If Python doesn’t find the library, the program will show an error in the terminal like this:

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'name here'`

This means Python searched for the library but couldn’t find it.

From now onward, we will use the word modules instead of just saying Python files, it gives us more of a developer’s feeling :) anyway.

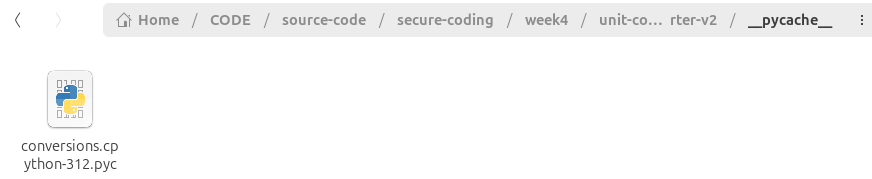

Why their is a __ pycache__ folder?

We didn’t even created this folder?? When you run a Python program that uses imports (like your main.py importing conversions.py), Python doesn’t just read the .py file directly every time. Instead, it first compiles your .py file into a faster, machine-readable format called bytecode. This bytecode has the extension .pyc (Python Compiled). Once the program is run, Python will automatically create this cache folder. You don’t need to work with this so ignore it.

In short, Python stores these .pyc files inside a cache folder called __pycache__. For example, if you have a file called conversions.py, Python will create first a folder __pycache__ and inside this their is a file(s):

conversions.cpython-312.pyc

conversions= module namecpython-312= the Python version (here I am using Python 3.12).pyc= the compiled file That’s it.

Run python3 main.py

All the logic for conversions is in one file conversion.py, and calls the functions from the main.py file.

Till now I think you have better idea how to write program in modules. Now to understand it more you need to practice it and do improve the unit converter project, move all functions to a separate file like I showed you, add one or two new functions as well (like meters <-> feet or kilograms <-> pounds) and then try to call it from the main python file, test your program with normal and weird inputs as well, what went wrong? and what you fixed? etc… Do practice these before moving to our next topic.

Error Handling!!

In the previous section, we explored writing code in multiple files, and this approach is very useful and important to follow. But as we move toward building real world programs, we need to remember that programs in the real world don’t always run under perfect conditions. Users might enter the wrong input, files may go missing, someone might divide by zero, or an attacker could deliberately try to break your program by providing invalid inputs instead of what is expected. If we don’t prepare for these cases, our programs will crash, which we don’t want since we are on a mission to write secure and clean code. So, let’s start learning error handling in python.

I want to explain the try and except in other word error handling in python in high level and a little kind of intermediate level below so try your best to understand.

Well python and many other languages like C++, Java, and JavaScript/TypeScript have an exception-handling mechanism that can handle errors and exceptional situations. First of all, I want to make a clear distinction between these two words:

“An error is something that can happen, and one should be prepared for it. An exception is something that should never happen.”

You define errors in your code and raise them in your functions. For example, if you try to write to a file, you must be prepared for the error that the disk is full, or if you are reading a file, you must be prepared for the error that the file does not exist (anymore). Many errors are recoverable. You can delete files from the disk to free up some space to write to a file. Or, in case a file is not found, you can give a “file not found” error to the user, who can then retry the operation using a different file name, for example. Exceptions are something you don’t usually define in your application, but the system raises them in exceptional situations, like when a programming error is encountered.

An exception can be raised, for example, when memory is low, and memory allocation cannot be performed, or when a programming error results in an array index out of bounds or a dict not containing a specific key. When an exception is thrown, the program cannot continue executing normally and might need to terminate. This is why many exceptions can be categorized as unrecoverable errors. In some cases, it is possible to recover from exceptions. Suppose a web service encounters a null pointer exception while handling an HTTP request. In that case, you can terminate the handling of the current request, return an error response to the client, and continue handling further requests normally. It depends on the software component how it should handle exceptional situations.

Errors define situations where the execution of a function fails for some reason. Typical examples of errors are a file not found error, an error in sending an HTTP request to a remote service, or failing to parse a configuration file. Suppose a function can raise an error. Depending on the error, the function caller can decide how to handle the error. In case of transient errors, like a failing network request, the function caller can wait a while and call the function again. Or, the function caller can use a default value. For example, if a function tries to load a configuration file that does not exist, it can use some default configuration instead. And in some cases, the function caller cannot do anything but leave the error unhandled or expect the error but raise another error at a higher level of abstraction. Suppose a function tries to load a configuration file, but the loading fails, and no default configuration exists. In that case, the function cannot do anything but pass the error to its caller. Eventually, this error bubbles up in the call stack, and the whole process is terminated due to the inability to load the configuration. This is because the configuration is needed to run the application. Without configuration, the application cannot do anything but exit.

When defining error classes, it’s often a good practice to define a base error class for your program. Then you can define more specific errors that extend from it. This makes your error handling cleaner and more predictable, but we’ll keep it very simple here instead of going into advanced enterprise level structures.

Here’s a simple example of defining and using custom errors in Python:

# A simple custom error class for our program

class MyAppError(Exception):

pass

class FileReadError(MyAppError):

pass

def read_file(filename):

try:

with open(filename, "r") as f:

return f.read()

except FileNotFoundError:

raise FileReadError("The file was not found, please check the name again.")

# Using our function

try:

data = read_file("data.txt")

print(data)

except FileReadError as e:

print("Error:", e)

Summarizing Error and Exception!!

In programming, an error usually means something expected might go wrong, like entering text when the program expects a number, or trying to open a file that doesn’t exist. These are things we should be ready for and handle gracefully. An exception, on the other hand, is raised when something unusual happens that breaks the normal flow of the program. In Python, both errors and exceptions are represented as “exceptions” in code, but conceptually, errors are often recoverable while exceptions are sometimes unrecoverable.

For example, if I ask a user to enter a number and they type in "hello", that’s not the program’s fault, it’s bad input, and we can recover by asking again. But if the system suddenly runs out of memory, there’s not much we can do. Our job as developers is to know which errors we can handle and which ones we should let the program stop for.

Now I hope it is clear, now let’s do learn and practice with some basics examples as well. By the way you can read and learn more about it from official python documentations: https://docs.python.org/3/library/exceptions.html

Using Try and Except!!

Python gives us a very clear way to deal with errors using the try and except . The idea is to write the code that might fail inside a try block, and then decide what the program should do if an error happens.

Look at this example.

try:

number = int(input("Enter a number: "))

print("You entered:", number)

except ValueError:

print("Invalid input! Please enter a number value.")

If the user types something like "abc" instead of a number, Python normally doesn’t know how to handle this. It will immediately throw a ValueError and stop the whole program with an error message on the screen. For someone a non programmer using the program, this looks like a crash and can be confusing. With the try and except blocks, however, we are telling Python: “don’t stop everything when you see this problem, just give control back to the user and let the user decide what to do.” In our example, we catch the ValueError and replace the crash with a friendly message to the user, such as “please enter a valid number.” This way, the program doesn’t die, and the user understands what went wrong and how to proceed further. This is the essence of error handling that instead of stopping the whole process, we recover from the problem, give feedback, and keep the program running.

Create Custom Errors!!

You know you can create your own error types? When our program or code go big it’s not enough to just rely on built-in errors. You can create your own error types by defining classes that inherit from Python’s Exception class. This makes it easier to raise and handle errors in a structured way.

class CalculationError(Exception):

pass

class DivisionByZeroError(CalculationError):

pass

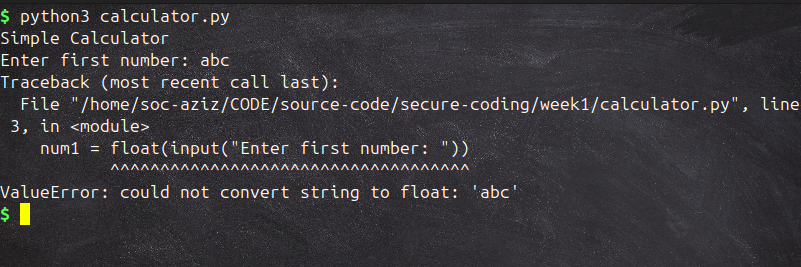

Now before moving to our weekly project first I want you to open our week 1 project calculator.py and run it and try to enter abc instead of numbers and then look what error we are facing?, will the program go crash or just show error? what is the error about? this error we explained above or not? etc. Ask these questions to yourself, you will learn alot practically and exactly I am showing now below in picture the kind of error you will face:

Now notice that we entered

Now notice that we entered abc, and the output error type is ValueError. This means the user entered a value that is not accepted or is invalid, which the program cannot handle, and that’s why it shows a ValueError. By the way, these are Python’s built-in error messages, such as ZeroDivisionError, ValueError, and others. Similarly, we can also create our own custom error messages with custom names and decide when to raise a specific error message.

Handling Multiple Errors!!

Sometimes, more than one kind of error can happen in the same piece of code. For example, let’s try dividing numbers:

try:

number = int(input("Enter a number: "))

result = 10 / number

print("Result:", result)

except ValueError:

print("That was not a number.")

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You cannot divide by zero.")

Here we are handling two different problems that might happen when running the code. The first possibility is that the input given by the user cannot be converted into an integer. When Python tries to convert something like "abc" into an integer, it cannot do that and immediately raises a ValueError. Without error handling, the whole program would stop and crash, but here we are catching this situation with except ValueError and showing the user a simple, clear message instead. The second possibility is that the user enters 0. In mathematics, dividing by zero is not allowed and not possible, so Python raises a ZeroDivisionError. Again, instead of crashing, we catch this specific error with except ZeroDivisionError and print a useful message back to the user. The nice thing about this structure is that our program now has separate branches for each kind of error, so no matter which problem happens, the program reacts correctly and continues running. This makes the code more reliable and the output more user friendly compared to just letting Python show its raw crash message.

There’s also one more piece you can add in these situations. The finally block. Code inside finally always runs no matter what happened in try or except. That means even if an error was raised and handled, or no error happened at all, the finally part will still execute.

To copy above code and paste, and let we add finally block. Example:

try:

number = int(input("Enter a number: "))

result = 10 / number

print("Result:", result)

except ValueError:

print("That was not a number.")

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You cannot divide by zero.")

finally:

print("This message always shows up.")

Where you need to guarantee something happens then use finally block.

So overall, our focus here is to learn and use error handling in our code to make it user friendly, protect the program from crashing, and ensure it runs smoothly. I hope you now have a clear idea of what error handling is in programming, especially in Python, and when to raise each error type.

Defensive Coding!!

Moving to our next topic which is about defensive coding approach. Defensive coding means always expecting that something might go wrong, and writing your program so that it cannot be easily broken. A good developer never trusts user input. Why? Because users will type wrong values by accident, and attackers will type wrong values on purpose. Defensive coding makes sure your program continues to run safely in both cases.

There are a few practices that help here. One is validating input before using it. Instead of directly converting input to int or float, we can put it in a function that keeps asking until the input is correct. Another practice is to never catch all errors blindly. You sometimes see people write except: without specifying the error type. This is dangerous because it also hides real problems. If your code has a bug, catching all errors will swallow it and you won’t know why your program behaves strangely. Instead, only catch the specific errors you expect and can handle.

Also, make your try blocks small. If you put ten lines of code inside try and an error happens, you won’t know which line caused it. Keeping the block small helps you isolate the problem and handle it more clearly. Python even allows you to use else with try/except. Code inside else only runs when no error happens, which keeps your logic organized. And finally, the finally keyword is useful if you want something to happen no matter what, like closing a file after reading.

Alright, now we are moving to our final project where we want to apply Error Handling and modular programming concepts, and at the end, we will test and compare it to our previous calculator.py program.

Calculator v2 - Mini Project

we are improving our project calculator.py from week 1 by applying Error handling and modular programming skills.

filename: operations.py

def add(x, y):

return x + y

def subtract(x, y):

return x - y

def multiply(x, y):

return x * y

def divide(x, y):

if y == 0:

raise ZeroDivisionError("Cannot divide by zero!")

return x / y

filename: main.py

import operations

print("## OUR PERFECT CALCULATOR ##")

while True:

try:

choice = input("Enter operation (+, -, *, /) to calculate or type 'exit' to quit: ")

if choice.lower() == "exit":

print("Exit Program!")

break

x = float(input("Enter first number: "))

y = float(input("Enter second number: "))

if choice == "+":

print("Result:", operations.add(x, y))

elif choice == "-":

print("Result:", operations.subtract(x, y))

elif choice == "*":

print("Result:", operations.multiply(x, y))

elif choice == "/":

print("Result:", operations.divide(x, y))

else:

print("Unknown Operation.")

except ValueError:

print("Invalid input, please enter numbers only.")

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

print("Error:", e)

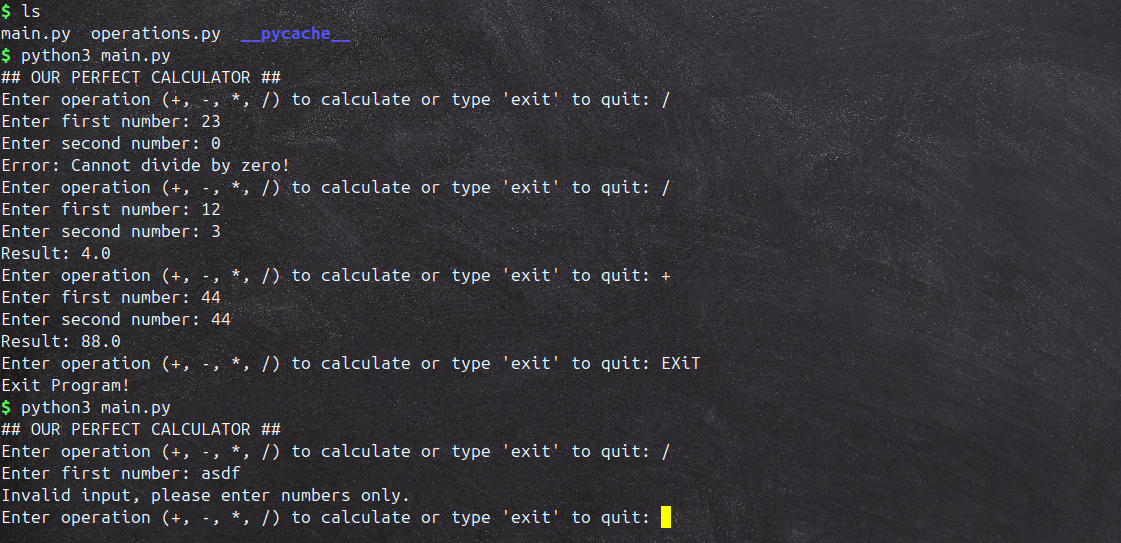

Output:

As you can see, our program is improving if you note some points like:

- It now supports the predefined

ZeroDivisionErrorand prints the result without breaking the overall program. - If we input

abc, it printsValueError, but the program still remains active and resets the previous state.

That’s the beauty of Error Handling.

Book Reading –> Chapter 2 (Threats)

Now, let’s start adding a bit of security thinking. In Designing Secure Software A Guide for Developers by Kohnfelder, Chapter 2, the author talks about The Four Questions we should ask when thinking about security:

I am going to summarize it for you to learn the important things from it is Adversarial thinking, why it’s important and what was the 4 questions:

- What do we want to protect?

- Who might attack it?

- How could they attack it?

- How bad would it be if they succeed? and then we have to apply on our software let’s say in our case we have built few mini projects now let’s we ask our-self how to secure it.

- What to protect?: The program from crashing or giving wrong results.

- Who might attack?: A user who gives wrong input, maybe by mistake or to break the program.

- How they attack?: Entering letters instead of numbers, very big numbers, or leaving input empty.

- What the Impact?: Program crashes, stops working, or shows weird output.

Overall Learning from Week 4

We learned that functions play a big role in making our code reusable and much easier to manage. Additionally we learned modular programming in detail by moving code into separate files, we also saw how projects become more organized and simpler to maintain as they grow. Next, we learned error handling which will always happen, but they should not crash our program, we need to learn to handle it. In python use try and except to catch problems and keep the program running smoothly. With defensive coding mindset, we can protect our program from both simple mistakes and intentional attacks. The main point here is never trust user input completely, always handle errors in a safe way, and think about how your program should behave when something unexpected happens. Another valuable lesson was the importance of thinking like an attacker from the very beginning, because it allows us to catch bugs and weaknesses before anyone else does. And finally, we realized that even small projects can break when given the wrong input, which shows that security starts with writing code that can handle these situations safely.

And with that said our chapter 2 from the book and week 4 of our series is covered. Please revise previous learning materials and try to practice, complete all the excercises and try to practice more and more. if still you you have any issues in topic and want to study more in depth then please do search for external resources. Next week our new topic will be File Handling and will be starting new chapter of the book (chap 3) as well (or maybe we just focus on code, I haven’t planned), so please stay tuned. If you have any questions, recommendations and improvement feel free to reach out to me on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aziz-u000/